Dallas Contemporary: Paintings about Paintings (25 Sep 2021 – 13 Feb 2022)

Holiday #13 & Holiday #14

For some reason, these paintings remained in the studio until recently. Again dragged out into the light of day, these works filled the artist with revulsion because all their light and energy have disappeared, the paint has yellowed, they are covered with dust, everything has been transformed into boring murk. And a new impulse emerged for the artist: to renew the series, to return to it once again those qualities that it once possessed, to re-inject those feelings of joy and exultation that were previously present and that were supposed to be there. It is possible that now, after the course of many years, he is compelled to realize these works. One could redo the paintings with rich, bright, emotional colors. But he has neither the strength, nor the time, nor the desire to do so. But the determination to make them cheerful and bright wins out. And he runs to the strangest method for injecting joy—namely, he sews on these flowers.

Time splits in these works. On the one hand, it is old hackwork, made as something remarkable but that by now has lost this remarkableness and is presented here as junk and vileness. And on the other hand, holidays have a place today as well, and demand at any cost that a joyful facial expression be hastily achieved. This is similar to many of our buildings, at one time decorated in intense rose or yellow colors, but over the course of many years they have been covered with dust and soot. However, often before holidays, painters would add another layer of rose and yellow “shininess” without first cleaning the dirt, and this film of shininess renews the past holiday.

The Six Paintings about the Temporary Loss of Eyesight (The Scene at the Square)

&

The Six Paintings about the Temporary Loss of Eyesight (They are Painting the Boat)

Why do these paintings have such a title, and did the author really develop problems with his vision?

No, there were no problems, and the appearance of gray dots on the whole surface of the paintings has a completely different justification. Any images of “reality” on the canvas don’t make them sufficiently energetically charged (that’s what the author thinks). In real life, such subjects may be interesting and curious, but when presented on the canvas they lose those qualities (if we don’t take into consideration the opposing opinion of the “realist” painters of the nineteenth century).

What kind of solution can be found in this case? We can go back to the experience with the paintings “Holidays” from 1980, where the elements foreign to the painting—paper flowers—are covering its entire surface.

This produces constant vibrational waves on the painted surface, creating in our subconscious an energy pulsation, which, as we mentioned above, will be necessary.

The gray dots in the new paintings substitute the paper flowers, and for an explanation of their strange appearance, we come up with the title, which speaks of a dangerous and sudden eye disease in order to bring into painting a new, dramatic effect.

Charles Rosenthal: The Three Riders, 1927-1928

&

Charles Rosenthal: The Auction, 1927-1928

C. Rosenthal, fictional personage, obstinately seeks, beginning in 1930, plots which would satisfy his yearning to create a significant work using his beloved Théodore Géricault as an example. At the beginning of 1932, these quests end with the creation of two paintings symbolizing the West and the East. The West for him is associated with the Park Bernett auction that took place in October 1931 in London, which Rosenthal attended as an observer. “I saw art as money…money and nothing more,” he would write later in his diary. Serving as the plot of his “eastern” painting was the gathering of horsemen for a hunt which C. Rosenthal might have witnessed when he visited Calcutta, where he found himself part of a geographical expedition. The spectacle of the three horsemen of the Apocalypse was filled with sorcery and threats.

“The presence of ‘whiteness’ in my early paintings is beginning to oppress me. I want to fill my painting entirely, to the very edges, without any remainders” resounds an entry in his diary around the same year. And yet, the simple realistic painting doesn’t entirely satisfy him. He supplements it with literary texts, placing tables with buttons in front of each of the paintings, uniting the narrative with the visuals, thereby anticipating many of the conceptual quests of the end of the twentieth century. Simultaneously, he introduces into the painting a dimension of time, as well as the appearance of a source of light not only in front of the painting, but also from beyond it, beyond the canvas. This unexpected device serves as the impetus for the creation of his subsequent works.

Three Fragments

The paintings consist of three parts, which are not connected to each other.

The first two parts have images, taken from different periods of time: the fourteenth century and the late twentieth century. In addition, a wooden circle depicting the face of a man is attached to the surface of the canvas. There is some kind of mystery in front of the viewer, a rebus to be solved. We give you one of the solutions.

Two fragments of the image are addressed to our cultural memory, and this memory tells us that we have two worlds, completely different in their artistic and historical significance.

One of them speaks of the sublime and significant. The other is about the banal, insignificant everyday. In any case, both speak of the past, which has little to do with us today and leaves us quite indifferent.

But the whole situation changes because of a little wooden circle with the image of a man. This man, who is looking directly at us, immediately produces an association with a mirror where the viewer is seeing himself. Thanks to this “mirror effect” we can see ourselves, at the present time, standing in front of the painting, but also being integrated into the subject of this painting. Somehow, we become the unwilling participant, a strange traveler in time. And because of this unexpected effect, the two times merge together and “The Three Fragments” is able to hold the viewer’s attention for a long period of time.

In the Museum (Ray from the Window) #1 & In the Museum (Ray from the Window) #2

1. Both paintings belong to the type of paintings called “The Curiosities” in the history of art. They have characteristic objects on their surface, which the artist meticulously painted there and which have nothing in common with the general context of those paintings. Why the artist painted them, what they were trying to tell us, remains an enigma for the viewer, demanding a certain effort of their mind. In classical paintings by Dutch, Flemish, and, sometimes, French masters, the same “curiosity” (the fly) appears numerous times, painted much bigger than its natural size. It looks like the artists are competing with each other in their detailed depiction of this insect. Each image also has a shadow projected on the painting.

As far as we know, the reason for appearance of this insect still remains unknown.

Maybe the artist and his client had a lot of flies in their spaces?

2. But let’s return to our paintings. There is no doubt that the rays of sunlight, because of their brightness and foreignness, prevent us from seeing the paintings and irritate us by their presence. We must try to understand the reasons why they are here. First of all, when we look at the painting, together with the sun beam in the middle of it, we see a stereoscopic effect: the ray of sun somehow gets separated from the surface of the painting and is hanging in the air, making us uncertain if it is even painted there. At the same time, the painting is not a flat image hanging in front of us and acquired an almost three-dimensional quality.

What is all this for? It’s not difficult to guess that we have variations on a baroque subject in front of us. In baroque paintings, the objects which are positioned on the first plane are brightly lit, and all the other objects disappear into the darkness. What is new in our positioning is that because of this curious method, not only separate parts of the painting are disappearing, but the whole painting completely immerses into the dark space, losing the light, lost in the faraway past on the edge of our memory.

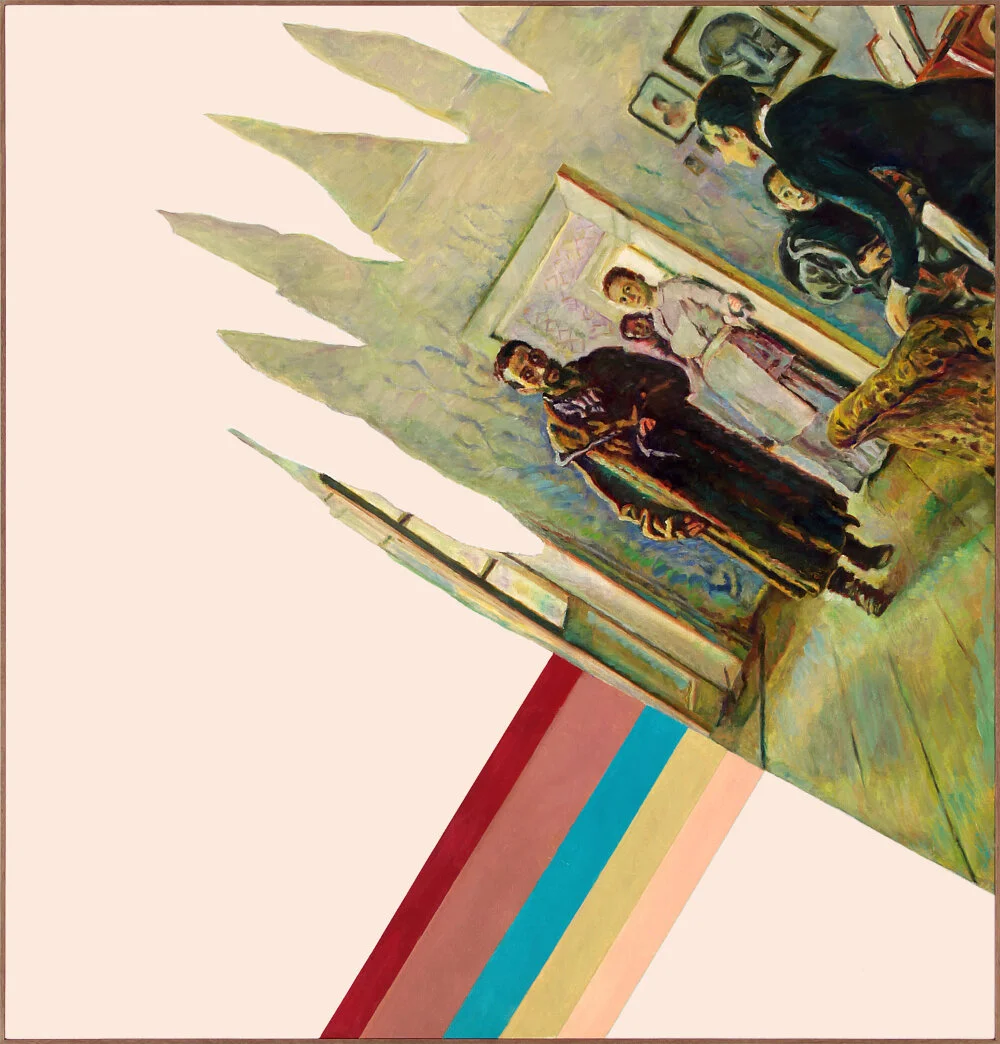

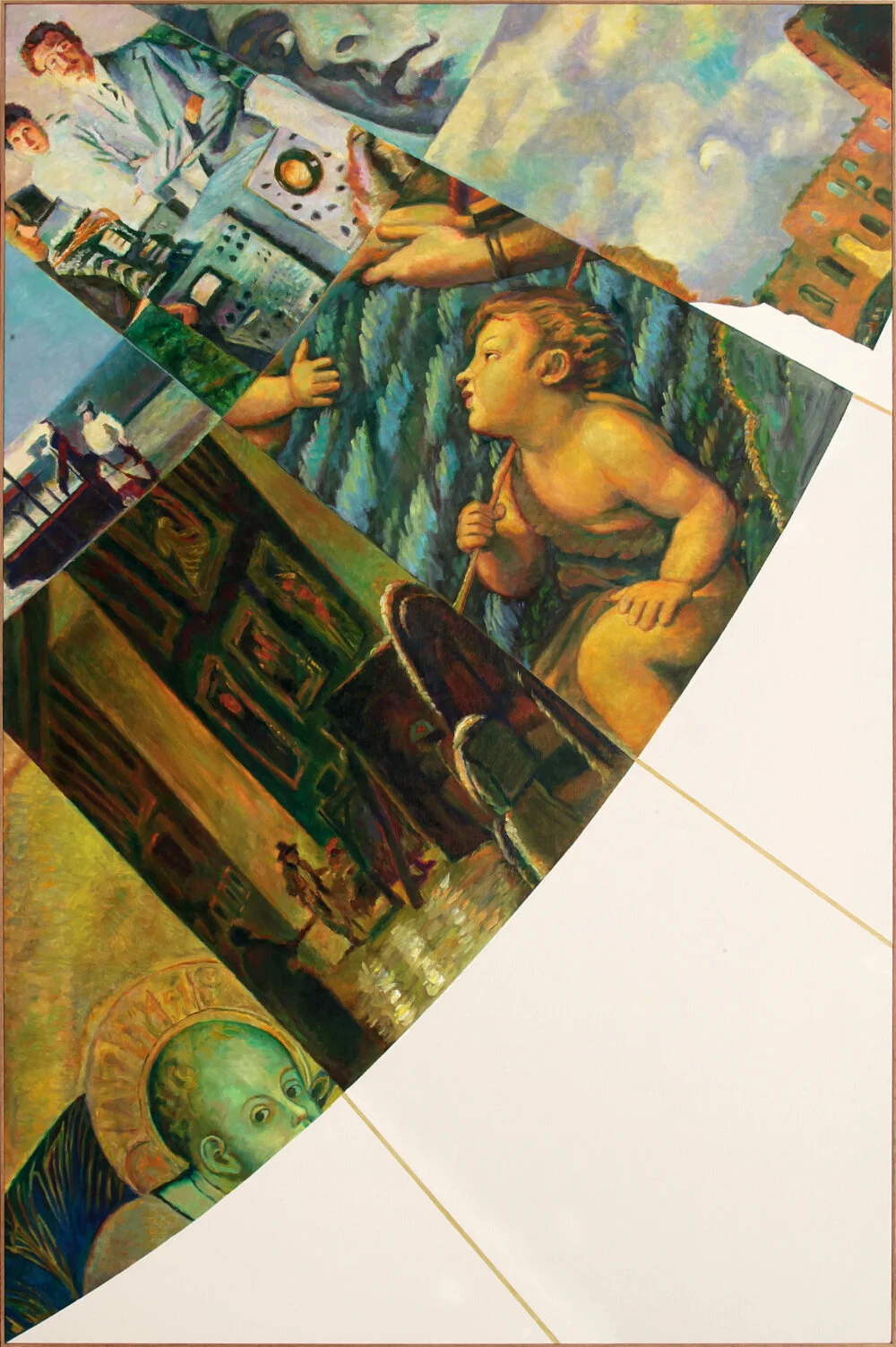

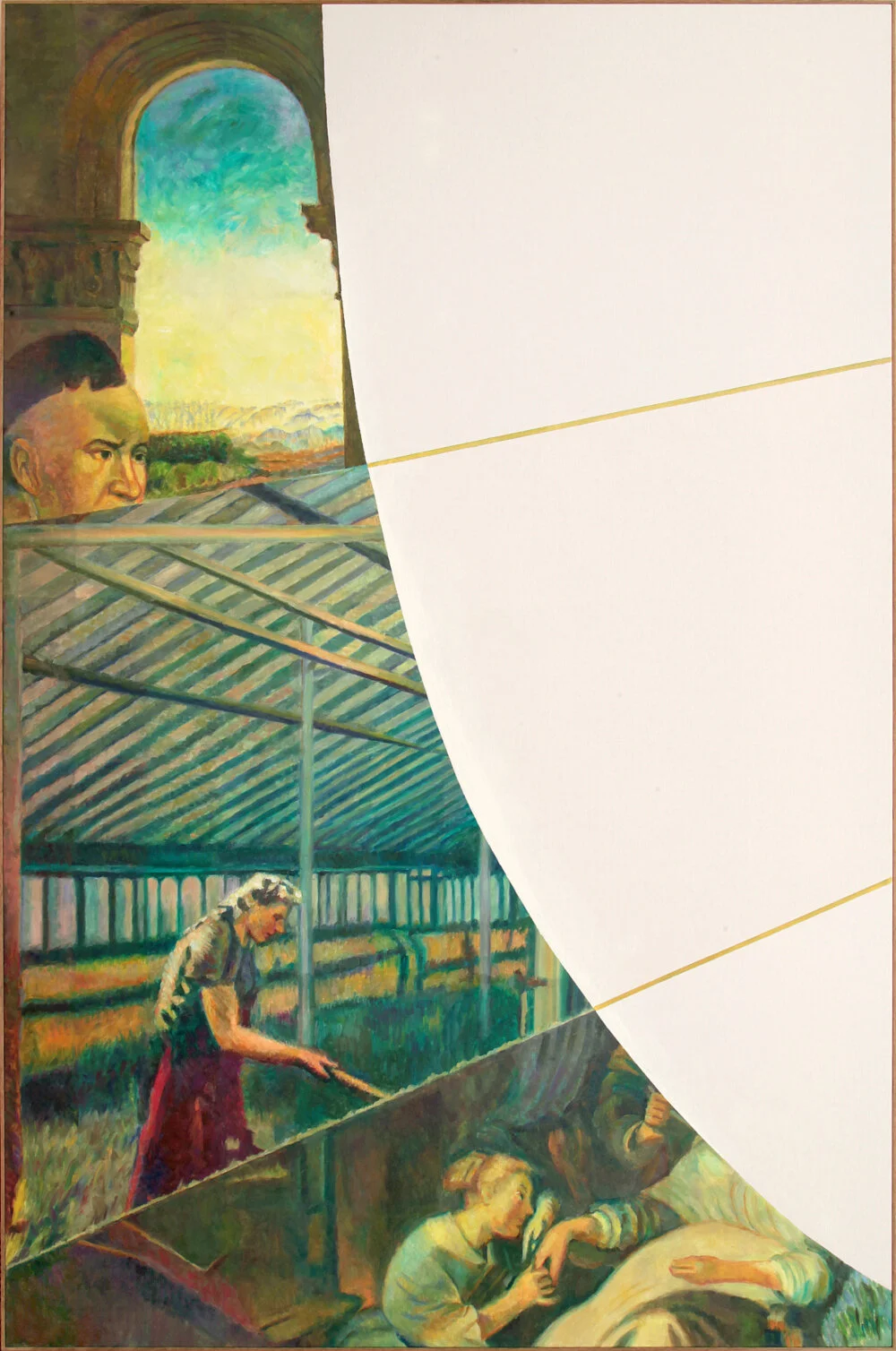

The Movement of Darkness #1-3

Each painting in this series consists of two separate paintings, which have a strange interaction between them: the left one is encroaching on the right one, and soon, obviously, the right one will not be visible at all. The left one demonstrates its movement with its ripped and sharp edges and because of this, its image becomes even more aggressive and dangerous. The contrast is visible in the images of both paintings: the left is darker, filled with sharp, stabbing lines. In the right one, which is much lighter, there are numerous pure colors, as well as soft, rounded forms. If we view everything collectively, we will see in front of us the intrusion of something gloomy and dark onto the world full of light and calm.

But what constitutes this darkness and light under our careful look? In the darker parts of the paintings we see contemporary, everyday, banal images: at the café, the scientific lab, the chicken farm. In the brighter part, subjects are from the middle of fifteenth century. But the deep contrast and, at the same time, the main meaning of this contradiction is that the images depict two different periods of history, which themselves produce distinct characters.

At the Studio #3

The subject of this painting refers to the famous masterpieces depicting artists’ studios: “Las Meninas” by D. Velázquez and “The Artist’s Studio” by G. Courbet.

The commonality between “At the Artist’s Studio” and “Las Meninas” is the presence of two main characters: a small girl and the artist at work. In the Velázquez painting, however, the girl is a stranger both to the studio’s world and to the artist. In “At the Artist’s Studio,” she is a lawful participant of the studio’s life. She is busy working and the difference in age between the two painters is the work’s main subject; one is at the beginning of her journey, the other at the end of his.

The similarity to “The Artist’s Studio” is no less interesting. They share a depiction of the artist in the background of the painting, which he himself has painted. The painting and the artist in it are painted in realist style. Because of that, the artist is “going” into his painting, becoming part of it. This is the deepest meaning, a precise metaphor: the artist, in the midst of working, transforms into a character of the world he has imagined.

As for the white triangle, which appears in the upper part of the canvas, we will present the explanation when we write “Commentaries for the Paintings, ‘The Movement of White.’”

He Never Came Back

Three subjects are depicted in this painting, each one separate and, at the same time, connected with invisible thin strands. Both painted portions of the canvas belong to different epochs: the one on the right belongs to the baroque, and the one on the left shows the inside of a factory from the middle of the twentieth century. The link between them is the chain of faces, passing through both halves of the painting, like a shared horizon.

But at the same time, this chain also separates them, accenting their differences, such as the shifts of the faces and characters, corresponding to changes in history and time.

The third subject in the work and secured to its surface are a pair of shoes and the green wooden fence, which seemingly have nothing in common with the painting. But the link obviously exists. It is visible in the title of the painting: someone, to whom belongs those shoes, is making two steps, in order to leave forever, to disappear from this world, regardless of his belonging to the long-past world of the baroque or to the recent Soviet one. He doesn’t like either of them. For him, they are surrounded by the fence, which is the reason he always wants to run away.

The Fishermen

It is well known that the modernists’ revolution at the beginning of the twentieth century changed realistic depictions to abstract images such as symbols, geometric structures (Mondrian), and grids (Jackson Pollock). The most important symbols, discovered by Malevich, were the square, the cross, and the circle. The general idea was that the representational world would never come back after the complete victory of symbols over the real.

But after Malevich, we once again returned to the images of reality, and ironically, we placed them at the center of a cross. The same may happen at the center of a square or at the center of a circle. It’s as we say: Never Say Never.

Two Fragments

This painting, like everything else, is turning the viewer's attention to his "cultural" memory, his preliminary knowledge of the history of art, in this particular case to the Russian art of the nineteenth and twentieth century.

But, simultaneously, we are talking about the encounter of realistic and abstract images. Both are positioned in a "floating" position relative to the painting’s vertical and horizontal axes. The tension is created by presenting the fragment of realistic painting in an inclined diagonal position, thereby violating its "normal" orientation of top and bottom. The viewer has a choice: Should they consider what was seen by Repin (and was only a “painting”) to be reality, or is this just empty space in which the scraps of their memories are floating around?

The Half of the Painting #23 & The Half of the Painting #24

Buddhists monks have a famous “koan” (a riddle): How do you clap if you only have one hand? In our paintings, only one part is painted and the other is empty. Nothing is there and therefore the painting as a whole simply doesn’t exist. To our minds comes the story about “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” as an example of a bold swindling.

But everything here, like in the story, is not so simple, not so obvious. Entering “the game” are such indirect elements as the geometric construction of the painting itself. The white, or empty part of it, by its space and size mirrors the part which is painted and the laws of symmetry start to work. The big role is played by the form of the painting, the pure square, where both halves are placed diagonal to each other and the thick frame, which unites all optical visions into one whole image.

All those indirect, but active elements, influence the ability for the imagination, hidden in our subconscious, to activate, and we start seeing the painted where it does not exist: “seeing, without seeing.”

It’s exactly the same as how the crowd around the Emperor saw his new suit because the Emperor himself did see it and transferred this vision to his people. Clapping, according to the Buddhist riddle did happen, but it did so only in the imagination of the pupil, through his inner hearing, which “woke” up and started to hear what others couldn’t. The sensible boy in Hans Christian Andersen story was then, after all, not completely right.

The Movement of White #2 & The Movement of White #3

In order to understand both paintings entitled “The Movement of White,” like the painting “At the Studio,” we have to connect them with a certain conceptual point of view, which, albeit in summary, we would like to present here. We are talking about the possibility that our world or whatever we perceive as and name reality, what we see, what we understand, study, and learn from, is only half of reality. The other half cannot be presented in any form. It cannot be understood, nor can our consciousness grasp it, but it does “live” and actively influences our reality and our existence.

But, after all, maybe it can be represented in the form of a “white” image, of “emptiness?” It is the backdrop of everything and sometimes “breaks” through the solid fabric, the surface of our existence.

Returning to our paintings, we can say that on the surface they remind us of old, partially faded tapestry, already ripped in some places. In those places, where the old fabric parts, striking through, shining, is that emptiness, this “white.”

In general, the painting is presenting itself as the artistic image, the metaphor for everything we discussed above.

Construction of the Cupola

Addition to the Painting Construction of the Cupola #1-5

Unexpected Solution

In late 2020, I started the painting “Construction of a Cupola.” As in every cupola structure, its construction goes in concentric circles that diminish as they get to the center. At the same time, we can imagine rays going from that center to the foundations of the cupola. The intersections of these rays and concentric circles form a grid and the surface of the cupola will consist of segments that gradually diminish as they approach the center.

So, in pondering my conception I prepared to make these segments one after the other, coming up with subjects for each, assuming that when I had finished them they would fill the entire surface of my cupola (its half) and simultaneously the entire painting.

I drew all the large segments on the edges of the painting and, following my sketches, began moving confidently to its center, filling in several smaller segments. And here I was ambushed by something strange and unexpected.

The point is that the planned painting was rather large (229 x 862 cm) and consisted of five separate canvases which would be put together for the final painting. I made each of the canvases separately, without completing them in full, but just marking in different places the diminishing segments on each canvas.

When I set all of them next to one another against the wall, just to see “how the work was going” and how much more needed to be done to fill in all the segments and thus complete the entire painting, I unexpectedly saw that the painting was “done” and that nothing more needed to be done!

What had happened?

Before executing all the segments, I had drawn thing yellow lines of the grid that I mentioned earlier and in which I had already completed the greater number of segments. So, when I put it all together, the white and the drawn segments formed a strange but convincing unity that led to the unexpected completion of the painting. The white, undrawn segments in that grid next to the “drawn” ones gained from that proximity a special, mysterious meaning that allowed them to take a “legal” place and not simply be unfinished “holes” on the surface; they had become natural participants of the entire artistic whole.

What was that meaning?

In the article “Finished/Unfinished,” I mentioned and examined the hypothesis that next to the “obvious,” real world there is something that we will never see and that in a symbolic, artistic image can be presented as being “white,” empty, incomplete. And now placed next to each other, “depicted” and empty, in the grid system, where they were the same size, their proximity formed that strange completeness, that unity that we can sense only intuitively.

How to Make Yourself Better

How do you make yourself a better, nicer, more agreeable person? This question of how to get rid of your faults and defects has been addressed by more than one generation of moralists, philosophers, and religious thinkers. Some people think it is possible to achieve it by changing the inner “me,” others by respecting moral rules, and still others by refusing earthly temptations. Personally, I have discovered a completely different possibility.

I made two wings out of white fabric and used leather belts to attach the wings to my back. After isolating myself and locking my door, I put on the wings. First, I spend ten minutes attending to my usual occupations. Two hours later, I take the wings off. I then repeat the procedure in the evening.

Very soon, this had positive effects on my character, and I discreetly started mentioning this invention to my friends and relatives. Prudently, I said that I got it from a scientific magazine. This way, it will be safer.