Life and Creativity of Charles Rosenthal

YEAR: 1999

CATALOG NUMBER: 144

PROVENANCE

Collection of the artist

NOTES:

This installation is part of installation No 180, “An Alternative History of Art.” See CRI, vol 3. pp 260-275.

EXHIBITIONS

Mito, Contemporary Art Gallery

Ilya Kabakov. Life and Creativity of Charles Rosenthal, 7 Aug 1999 — 3 Nov 1999 (Organisation: Contemporary Art Center, Mito)

Frankfurt am Main

Ilya Kabakov stellt vor: Leben und Werk von Charles Rosenthal, 11 Dec 2000 — 4 Mar 2001

Chemnitz, Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz

Ilya Kabakov – 50 Installationen, 23 Mar 2001 — 4 Jun 2001 (only Auction and The Riders)

Центр современной культуры «Гараж» / The Garage Center for Contemporary Culture (since 2014: Garage Museum of Contemporary Art), Moscow, Russia

(As part of installation No 180, “An Alternative History of Art”)

Илья и Эмилия Кабаковы: Московская ретроспектива / Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: Moscow Retrospective, organized by The Ministry of Culture and Cinematography and The Moscow Biennale Foundation, September 17 to October 19, 2008

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

(As part of installation No 180, “An Alternative History of Art”)

The paintings were exhibited as a unified group of works in Frankfurt, Germany, in 2000: Ilya Kabakov stellt vor: Leben und Werk von Charles Rosenthal 1898–1933 (Ilya Kabakov Presents: The Life and Creativity of Charles Rosenthal 1898–1933), December 10, 2000 to March 4, 2001, and in Cleveland, Ohio, USA, in 2004: The Teacher and The Student: Charles Rosenthal and Ilya Kabakov, Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland, September 9, 2004 to January 2, 2005

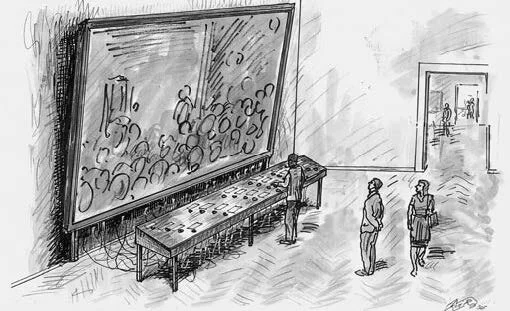

CONCEPT AND DESCRIPTION OF THE INSTALLATION

The installation represents a retrospective of the works of a ‘famous’ artist, a detailed exhibition of his works – drawings, sketches, paintings from various periods of his life: the beginning, his mature period, and the late, final stage of his creativity. Each period and the main works, as expected in a posthumous retrospective, are accompanied by detailed commentaries, details of his life and biography, quotes from his statements about art. Hence, before the viewer is a classic exhibit-retrospective, similar to an exhibit of Mondrian, Seurat, Manet, etc.

But this ‘artist’ is entirely fictitious, he never existed in reality. All of his works have been created by the ‘hidden’ author of the installation, Kabakov, who is supposedly acting in the role of the ‘curator,’ having collected and exhibited this ‘retrospective’ consisting of not less than 78 paintings, objects, and 150 drawings.

What is the point of the creation of such a multitude of works, and moreover, the creation of a fictitious author-personage?

The meaning emerges in the consciousness of the viewer when he, passing through the suite of five large halls running one after another, reaches the last, final hall. Before him is the completely clear history of the development of the ‘artist’s’ creativity, beginning with his early and ending with his late works, clearly divided into three stages.

In the beginning of his creativity (the first hall of the exhibit), the theme of the ‘emptiness’ and ‘whiteness’ emerges and begins to ‘resound’ distinctly among diverse plastic ‘experiments’ of the young ‘artist.’ But it emerges in this period as more of a background, as a special quality and characteristic of this artist which the artist himself doesn’t quite yet sufficiently realize and it isn’t posited as the main problem worthy of attention and elaboration.

That’s why it is easily muffled by other problems (the second hall) and among them, the ‘problem’ of realism in art, the task of how accurately to reflect the current surrounding life in the form of that very life, i.e. the means of realistic depiction. Here emerge ‘realistic’ subjects, real figures, a lofty perspective and other devices of ‘veracious’ depiction of the surrounding world. That world ‘surrounding’ the artist seizes his imagination more and more. (There are 10-42 paintings of such content on the walls of this hall.)

But the ‘veracious’ depiction of life only by visual means also ceases to satisfy him. He searches for forms whereby a narrative, a story, could be included in the plastic painting: he searches for a means of uniting painting and literature. The result is two enormous paintings 4 x 7.5 meters in size (the third hall), where such a resolution is realized in the paradoxical form of combining realistic depiction with a moveable music-stand holding a narrative commentary. It is as though these two paintings with music-stands comprise the middle period in the development of his creativity, after which it moves in another direction, gradually changing its content.

It changes in the sense that the artist gradually, but unwaveringly, loses interest in the depiction of everyday reality. This, perhaps, is connected with a loss of interest in his actual real life, so to speak, in connection with his age and various life and family circumstances. His inner world attracts him more and more, a departure into himself, searching for his own inner path concealed from others. Parallel with this is a diminishing of interest in ‘realistic’ depiction in ‘his’ paintings (fourth hall). More and more, these realistic depictions become for him a thin film which in places breaks through, and from behind it, emptiness, a gaping void looms larger and larger.

The final hall of the exhibit (fifth) is the final, last period in the creativity of the ‘artist.’ On large, almost empty white canvases, there remain virtually no traces of the external world, and the very quantity of depicted elements on it is very small. The entire hall represents a separate, integrated installation, a unique meditative space consisting of white walls, white large canvases, and white light shining on them from above and flooding the entire space all around. The entire hall affects the viewer as a united whole which should submerge him in a special state of peace, tranquility and lucidity, where he can immerse himself in peace and meditation.

In this way, our fictitious author arrives toward the end at the creation not only of paintings, but also of an integrated installation from them which forms and creates the atmosphere of a unique temple. The author proposes that the viewer enter and feel what he himself experiences and feels at the end of his life, at its unique conclusion.

The arrangement of the halls in the Mito Museum, their dimensions and lighting, couldn’t be better for the realization of such a concept.

About Charles Rosenthal (1898-1933)

Brief Biography

The biography of the artist Charles Rosenthal, who died at an early age, is not rich in events, and it is typical for the majority of artists living at the beginning of our century. We have rather meager evidence about his early years and education. It is known that he was born in 1898 in Kherson, in the Ukraine, into a middle-class Jewish family. His real name was Sholom, and he was the eighth child. His father was a photographer who had a small photo studio where he would produce portraits of residents from neighboring streets. Little Charles would help his father in retouching the photos, but when he had grown up some, he was taken to Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) into a family of rich relatives who didn’t have any children. In 1914, having passed the exams, he entered the Shtiglitz Art-Trade School, where over the course of four years he studied painting, drawing, and composition, acquiring the fundamentals of the ‘realistic school.’ In 1918, under the influence of new artistic trends and opportunities that had emerged immediately following the proletarian revolution, Rosenthal left for Vitebsk and entered the art school there organized by Marc Chagall (this school was later directed by Kazimir Malevich who had been invited there for that purpose). Having become acquainted and enthused with the theory of Suprematism, he did not agree with it entirely, and when the teacher left for Petrograd in 1922 with his loyal students, Rosenthal, following the example of many young artists, decided to leave for Paris, the Mecca of artistic life of that time. Having virtually no acquaintances, experiencing unbelievable deprivations and difficulties, he still continued his independent artistic quests, searching for his own path among the enormous multitude of ‘directions’ surrounding him. The profession of a retoucher, the skills he acquired in childhood while helping his father, helped him to survive. Despite his persistent, selfless efforts, he was not able to achieve even the slightest recognition or attract even some small attention to his paintings. Perhaps a certain role, even a fated one, was played by the circumstance that, in contrast to his colleagues, Sholom (he changed his name in Paris to Charles, a more familiar one for the local ear), continued to hang on to the images of that reality which he had abandoned long ago, not paying much attention to the new life surrounding him, trying to recreate what was then going on in Socialist Russia. It is difficult to say how his fate might have worked out in the future if it hadn’t been for the tragic event that occurred in April 1933: the artist died on a slope of Montmarte under the wheels of an out-of-control automobile.

The artistic legacy of Charles Rosenthal is relatively small: around 78 paintings and more than 150 drawings. Nonetheless, these were preserved entirely thanks to the fact that after his death they were taken by one of his few admirers, Luke de Vries, and were preserved at his estate near Charenton, avoiding in this way all the vicissitudes of the war and post-war period in France.

The works of Charles Rosenthal began to attract more and more attention, primarily because they pose a series of puzzles to the attentive researcher. Many of the questions and problems that he tried to resolve in his work seem particularly relevant and profound today. The thoughts and utterances in his diary entries are also quite interesting and provocative, and his persistent interest in the romantic ‘school,’ particularly in Géricault (to which he dedicated entire pages), sounds unusual against the backdrop of the universal interest in modernism, in the art of the future.

The current exhibit of Charles Rosenthal, in addition to its display of a great and original gift, will permit a new look at the complex and ambiguous processes in art at the beginning of the century.

General Issues in the Work of Charles Rosenthal (1898-1933)

In the current state of art knowledge, it is accepted to look at the works of Charles Rosenthal in terms of three problems, three issues. These questions are so actively provoked by his work, so clearly and unambiguously posed by him, that in the language of contemporary art history they are referred to as the ‘problems of Rosenthal,’ or the ‘case of Rosenthal.’ It must be said that it is not only critics and artists who are now interested in these ‘problems,’ but also psychologists, psychoanalysts, theologians, oculists – scholars who, it seems, are from fields not closely related. The ‘case of Rosenthal’ has gone far beyond the border outlined by the world of art museums, galleries and exhibit halls.

Problem I. The depiction of what the artist sees with a ‘simple eye.’

During the time of his birth (the end of the 19th Century), and because of the nature of his artistic education, Charles Rosenthal belongs to what is usually referred to as the realistic school (it presents perceptions of the world in a realistic form of depiction). The world is presented as it is seen by a person’s eye endowed with simple, natural vision. The consciousness of the beginning of the century called for a refutation of this, that this ‘simple’ vision not be trusted, but rather that we reveal and see what is located in the depths, ‘beyond’ the ‘simple’ surface of apparent reality. This refutation and the vision of something ‘other’ became a mandatory requirement of the new consciousness that was supposed to break once and for all with the old, ‘non-real,’ ‘optically’ deceptive painting of the past. But the ‘case of Rosenthal’ represents a rather strange and intermediary type of visual perception of the world during that epoch rarely met in pure form. If what was characteristic for the normal artistic and realistic perception of a person of the 19th Century was a complete, whole view of the surrounding world, then for Rosenthal this world, expressed on his canvasses, looks as if it has holes in it, as if it is partial, fragmentary, full of ruptures. This is despite the fact that the artist is trying with all his efforts – and this is in virtually every work – to make the painting whole, stretching out across the entire surface of the canvas. But each time, despite all these efforts, he doesn’t manage to do this. He believes in this ‘simple vision,’ believes that he will achieve this in life and in his art, and considers his constant failures to be the result of either his visual or psychological shortcomings.

Such was his attitude toward contemporary artistic directions. He is filled with great respect for them, especially for Suprematism. But he doesn’t understand why, moving toward a new horizon, one must so radically and mercilessly destroy the past; why it was forbidden, at least partially, to take it with you; why this new system, if it wanted to become complete and all-encompassing, could not allow a place for that world which it had ‘overcome’ and which had been, in essence, not quite so bad. Understandably, in his quests he tried to resolve this paradox, this dilemma, searching for a place for the past in the new emerging situation.

Problem II. Completeness and incompleteness.

In the diaries of Charles Rosenthal, beginning with the very earliest entries, one and the same motive keeps repeating itself: the impossibility of continuing and finishing a work already begun (we are talking here, as always, about a painting already begun). The author experiences this absolutely tragically, gradually, to his great grief, elucidating for himself the reason. We find it in the notes of 1915 – that is, around the time of his studies in the art institute. To the professor’s question as to why he could not forge ahead with his paints toward the center of the canvas and why the painting remained in the same state it was in a week ago, Charles answered: “The more I draw, the more I hear a sort of prohibition ‘against the destruction of the white surface.’ The more I ‘advance’ on the white, the more the ‘white’ resists and doesn’t allow me to.” Another entry in the diary reads: ‘The most surprising thing is that my eye sees this white surface as more and more active and important. My eye sees that which I bring to it and draw near it as more and more insignificant and unimportant, something that, in fact, doesn’t need to exist at all.’ And another entry reads: “The main thing is this whiteness. I look at it with love and admiration and at what I draw on it as unnecessary and almost criminally bad; in a literal sense, a ‘dirty’ thing.” (Entry for April 14, 1917.) The artist is perpetually oppressed by his inability to cover the canvas, to overcome the ‘white delusion.’ He appeals to various doctors, considering this to be some sort of special, rarely encountered defect in his vision. His trip to Paris is in part connected with the desire to visit and seek the advice of local oculists and ophthalmologists. ‘Miserable vision,’ ‘a semi-blind monster’ – this is how the artist refers to himself in letters to his mother. From these same letters we learn that he begins a large number of his paintings with the hope that in the future (after, so it seemed to him, he could eliminate this ‘accursed’ defect of his), he would manage to continue and finish them. But there was a great quantity of ‘started’ (begun) paintings, and the sudden, tragic death of the artist transferred his entire legacy to a realm of a completely different ‘discourse’ of analysis, it placed the problem of ‘completeincomplete,’ ’finished-unfinished’ – in other words, ‘success-failure’ – at an entirely different angle. The ‘riddle of Rosenthal’ today is discussed as an argument on behalf of the ‘concept of execution,’ a ‘demonstration of the open process over its dead endpoint.’ In the art of Rosenthal, completeness and incompleteness are ambivalent, they trade places. The dynamics of the relationship are preserved in them. In the opinion of certain specialists, they stimulate the viewer to join the process, to uncover more and more associations and contexts, to sort through and find unexpected variations of the resolutions. And the meeting of the familiar with the unfamiliar (begun realistic fragments of painting with emptiness, with the mysterious ‘whiteness’) that comprises the main plot, the basic subject and tense drama of the artistic legacy of Charles Rosenthal, turns out to be particularly stimulating.

Problem III: Light from without and light from within.

The third ‘problem of Rosenthal’ is no less curious. Just like the first two, it has engendered numerous commentaries on his work. We are talking here about the interpretations of whiteness in his paintings as a contractor of luminescent energy, as ‘whiteness’ containing not merely white paint or serving as a surface on which there is nothing, but rather as a fundamental screen reacting to the emanation, to the flood, of luminescent energy.

We again turn to the artist’s diaries. The entry for 1913, that is, the time of the very beginning of the period of creativity, reads: ‘As soon as I commence working, whether on a canvas or on a drawing, I feel that I am being irradiated from behind by an intense light, to which I react acutely, painfully. The light of day or a lamp in the evening forcefully hits the canvas or paper in front of me, and it suddenly becomes a strange mirror of light at which it is painful for me to look.’ ‘A white canvas is a concentration of the light of day, and any depiction only clouds and ruins it’ – we read in another place. But toward the end of the 1920’s the sources of light in relation to the canvas begin to change places, and Rosenthal begins to ‘see’ distinctly that the light is coming toward him from beyond the painting, from the very depths of the canvas. Here is a fragment on this subject (September 13, 1932):

“From beyond the entire surface of the painting moves or (it would be better to say) flows with a steady, warm, overflowing, sort of granular light. I feel that it is coming from the infinite ‘distance,’ it envelopes me and departs behind me, not losing either its power or energy. It’s as though I am swimming in this radiation. Everything that I depict in a painting I see first submerged in this light. They, these depictions, slowly move around in it. Like dust particles in a sunbeam, they lose the distinctness of their outlines, and their materiality becomes flat, transparent. If something is drawn with a black contour, then I physically feel how the ray, filled with tension and power, pierces all the spaces between the black lines and flows toward me with even greater force!!”

What kind of light did the artist see while working on a canvas? Did he begin to ‘fall into’ a strange, ‘semi-mystical’ state? And how should the viewer perceive the paintings done with such an interpretation, such a conviction? Should he force himself to ‘see’ this light instead of the empty whiteness not drawn on the canvas? Should he believe and fall under the influence of ‘white shamanism’? And of course, considering these final diary entries, how should we view the large group of his late works with crates – as white screens filled with ‘inner light,’ or as a series of conceived but only barely begun works interrupted by the sudden, tragic death of the author? The vision of this kind of light is such a private, intimate experience that the perception of it as a whole depends on the viewer’s verification: on one and the same white canvas he can see both the light that the author ‘saw,’ and absolutely nothing, zero, total emptiness.

Images

Literature