Incident at the Museum or Water Music

YEAR: 1992

CATALOGUE NUMBER: 60

PROVENANCE

Collection of the artist

NOTES

Musical arrangement by Vladimir Tarasov

EXHIBITIONS

New York, Ronald Feldman Fine Arts

Ilya Kabakov: Incident at the Museum or Water Music, 12 Sep 1992 — 17 Oct 1992

Chicago, Museum of Contemporary Art

Ilya Kabakov: Incident at the Museum or Water Music, 10 Jul 1993 — 21 Sep 1993

Darmstadt, Hessisches Landesmuseum

Zwischenfall im Museum oder Wassermusik, 17 Mar 1994 — 5 Jun 1994

Barcelona, Fundació Antoni Tapiès

Els limits del Museu, 14 Mar 1995 — 5 Jun 1995

Lisbon, Centro de Arte Moderna (José de Azeredo Perdigão) da Fundação Gulbenkian

Incident at the Museum or Water Music, 31 Aug 1995 — 22 Oct 1995

Paris

Visions du Futur, 5 Oct 2000 — 1 Jan 2001

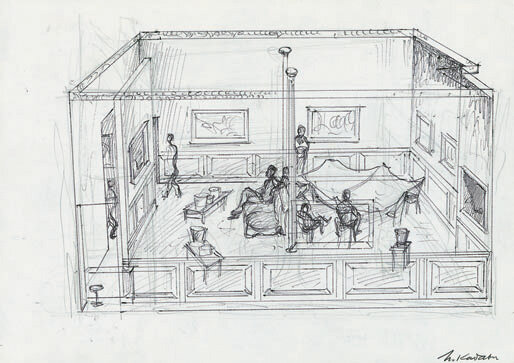

DESCRIPTION

The exhibit consists of two large galleries of an old, respectable museum with a very good reputation, similar to the Louvre or to London’s National Gallery. The walls of one of the halls are painted a dark claret color; the walls of the other hall are a noble pale green. Under the ceiling is a white molding like a ribbon; at the bottom, the walls are separated by dark wooden panels. Along the walls, more than a dozen classical dark, very good paintings, 120 x 170 cm, are hanging in gold or dark black frames.* The lighting, as is customary in old museums, is dull, subtle. The light is concentrated on the ‘masterpieces’ that are hanging around the room. In the center of both rooms are chairs and couches for intense, tranquil contemplation of the art.

It is very unfortunate, but that morning an extremely unpleasant incident occurred at the museum. When the employees undid the sealed doors and were getting ready to open the doors for visitors, they saw that the entire floor in both halls was covered with water, and that water was streaming down from the ceiling in various places. Either the roof didn’t withstand a strong downpour, or else the neighbors upstairs didn’t turn off the water, but the soaked ceiling was threatening to cave in, and the sparklingly polished floor could swell up and warp at any minute.

This is all to say nothing of how terrible it is to think about what might have happened in such a situation to the works of art hanging in the museum. Initial ‘fire’ measures are taken. ‘Circles’ are arranged out of the chairs around, particularly dangerous places. A plastic film is stretched over the chairs and a hole is punched in its middle so that the water could run into the bucket placed under it. There, where the streams of water were smaller, jars are placed, troughs, everything that could be found at the moment.

And the quiet of museum halls is suddenly transformed into a strange music, a music of falling water. Streams and drops in various ends of the halls form a complex, multi-voiced polyphony, wherein contemplated combinations the low ‘voices’ of the streams, beating the stretched plastic like a drum, combine with the ‘bells’ of the droplets which are falling into the metal buckets, with the ‘staccato’ of the glass jars and the slow, rhythmic blows in the large, metal trough.

The floor is wiped up, the employees have left. A few chance visitors, who in the commotion managed to enter the museum, wander amongst the strange and incomprehensible ‘objects’ that are placed here and there. Only a few of them, those who suddenly were able to appreciate the combination of the high ceremoniousness of the surroundings and the magical, unusual sounds, take the free chairs, place them around the ‘musical instruments’ in such a way that, just like in the conservatory, they can engross themselves in the world of the slightly sad, but at the same time, high and flourishing harmony that is so unexpectedly resounding here.

Commentary I

The main theme of the installation Incident in the Museum or Water Music is served in part by the situation described earlier of the The Empty Museum. The visual perception of the surrounding space (just like in The Empty Museum, but this time with paintings actually hanging on the wall) is replaced by the musical perception of it, whereby the very same dwelling suddenly becomes a concert hall as a result of this altered perception. Moreover, this ‘shift’ occurs via a simple shift of attention which can concentrate itself freely, by its own choice, first on one and then on another aspect. It is necessary to tell a bit about the installation in order to understand what we are talking about. The installation consists of two halls and a corridor where an old ‘classical’ museum is constructed, similar to The National Gallery in London. One hall has dark-brown paint on the walls, the other – velvety-green; a soft ‘museum’ light illuminates the fourteen paintings of average format in black lacquer frames. In the middle of the hall, there are dark, soft couches, gold-gilded cornices under the ceiling, wooden panels along the walls. It is a normal old museum, a normal concentrated, stifled atmosphere. On the walls, there is ‘normal’ painting, not particularly good and not particularly bad.

The plot twist creates the unexpected shift in this installation, a new situation. According to the scenario, the ceiling has started to leak all along the perimeter of the museum, and the entire place is filled with the sounds of flowing streams and drops of water falling into buckets and pails which the administration luckily has placed on the floor all around the hall because of the misfortune. Sparse loud pings in the aluminum buckets and pails, the frequent ‘drumbeat’ of a large basin, the rustling of the water on the plastic stretched between the chairs – all of this forms the general sound of a developing catastrophe. But all it takes is for the visitor to shift his attention from this horror happening in the museum, from the containers standing in all the corners and the stretched plastic, and instead to concentrate on the musical sound of this noise, and it suddenly becomes a richly and intricately organized concert, a polyphonic play in which the sound of each ‘musical instrument’ is precisely calculated and arranged: the low-timbred plastic, the high ‘voices’ of the glass jars and enamel mugs. This musical play consists of two parts, each resounding in its own hall. In the red hall is the active, major part; in the green hall is the tranquil, meditative, minor part constructed on the intermittent arhythmic pings of the droplets into shallow aluminum pans and into a large iron basin. This entire original musical play, as well as the system of water pipes under the ceiling and floor, was created by the composer, Vladimir Tarasov, who organized this entire system in such a way so that the installation, throughout its entire existence, could constantly maintain the same musical resonance. The general content of the installation, the metaphor contained in its basis, is easily read: what is catastrophic for the museum is good for the total installation as an artistic whole in which everything exists in a unified complex. Chaos on one, lower level transforms into harmony on the next, higher level. The sudden switching of our consciousness, a different accommodation of our internal vision – and we see another picture: minus changes to plus, even though the original situation remains the same. This duality of the reading includes a fastidious pair – sound and visuality – in a continually functioning ‘figure 8’: on the one hand, the noise of the water and the surrounding chaos interferes with the contemplation of the paintings (the very reason that people have come to these halls); on the other hand, the ‘water music’ is very nice and harmonious if you concentrate on it and listen to it separately, but then the entire visual dimension hinders us, including the paintings, the gold gilding, etc. But this is all understandable, both the first (‘museum’) and the second (‘musical play’) are specially concocted. In reality, there is no museum at all, the paintings are dubious (they are more likely bad than good), and they were done by some invented figure. In any case, they would not be hanging in a ‘normal’ museum. And the music, in essence, is water from a leaking ceiling and nothing more, and perhaps we only imagined that we heard its structure and harmony.

The viewer swings back and forth on this pendulum of meanings; the ‘figure 8’ traces newer and newer loops.

Where is the synthesis of this dialectical pair? It is in the peculiarity of the total installation genre, whereby all the diverse components comprising it receive their resolution. This is, in fact, the sought-after synthesis in the infinite system of theses-antitheses which fundamentally comprises any ‘total’ installation.

And finally, about the 14 paintings that hang on the walls of the museum. They belong to the brush of an invented artistic figure, S. Y. Koshelev, who in truth occupies a place in the museum.

Commentary II

(Author-figure S. Y. Koshelev)

Sergei Yakovlevich Koshelev, having been born into a family of a village teacher in the village of Pokrovsk in the Barnaul Province, came to Moscow in 1904 after the death of his parents to live with a family of distant relatives on his father’s side, and at the wish of his adoptive parents, he entered the Commercial School. But a business career did not attract the talented youth. His innate talent for drawing lured him to visit the many art museums, collections, exhibits that Moscow was so rich in at the beginning of the century. At one such exhibit, he met Dolgushin who was at that time a teacher at the Moscow School of Sculpture and Architecture. The young provincial boy, who virtually hadn’t held a palette in his hands until that time, brilliantly passed the entrance exams and enrolled in the course of one of the most famous Russian artists of that time – V. A. Serov. The country at that time was full of anticipations of changes, and this couldn’t help but touch the youthful student. Koshelev and four of his classmates are expelled from the walls of the school for participating in revolutionary meetings. A period of wandering and searching for an independent path in art began. Fall 1917 found Koshelev in Paris, where he had arrived a year earlier to get acquainted with the Paris school of painting. But new movements – Cubism, Fauvism, Dadaism – did not captivate him too much. In his words, “[I] belonged completely and forever to my idol,” Paul Cézanne, who had opened for him, and not only for him, the horizons of painting, the domain of color. For Koshelev, Cezanne remained the ideal of an artist for the rest of his life after his return to Russia.

From 1918, Koshelev devoted himself to the restructuring of the artistic life of the young republic. He participated in numerous commissions, he worked in the exhibition department of Narkompros (People’s Commissariat for Enlightenment) and taught at VKhUTEMAS.**

His pedagogical activities must be spoken about separately. Immediately after the revolution, he chaired the Department of the Analytic Method (a similar department was opened in Petersburg, headed by Filonov). Under his leadership, a large group of graduate students and students worked right up to the closing and reorganization of VKhUTEMAS in 1932, which thereafter was called the ‘Koshelev Academy.’ Even against the background of such famous VKhUTEMAS studios such as the studio of Tatlin or Falk, the ‘Koshelev school’ attracted the unremitting attention of students and faculty of VKhUTEMAS, inspiring numerous arguments and discussions.

What was so unexpected in Koshelev’s ideas and pedagogical method? It is generally known that the characteristic sign of the epoch under discussion was the large number of the most diverse, ‘left’ and ‘marginal’ artistic trends, with each of them insisting, with all its ‘revolutionary’ fervor, on its own legitimacy and its exclusive right to represent the new epoch and the birth with it of the ‘art of the future.’ Their irreconcilability toward others and their complete rejection of that which was ‘not their own’ was equally characteristic of the ‘Rayonists’ (Larionov), the ‘Constructivists’ (Rodchenko, Stepanova), the ‘Suprematists’ (Malevich), and many others.

Koshelev proposed his completely original method for creating painting as a movement. In the literature of art history, Koshelev’s method has been assigned the term ‘Synthesism’ (from the word ‘synthesis’), although Koshelev himself preferred to avoid this term in his own lectures and classes. The essence of the method rested in the following: not to distinguish any individual problems or tasks from the practice of painting (and this is precisely what virtually all of Koshelev’s contemporary colleagues were doing), but rather to try to ‘synthesize,’ to unite, all these methods into a singular highly artistic alloy, where all these issues that were examined and developed by others separately would be united into one harmonious counterpoint, into a ‘complex knot,’ as Koshelev himself called it. Nothing, according to this method, should be discarded, but everything should find its place: the ‘realism’ of the Peredvizhniks, the ‘formalism’ of Cézanne, the ‘genrism’ of Menzel, the ‘air’ of Corot. As a result, a certain ‘ideal painting’ was to emerge, and the goal of its creation, according to Koshelev’s idea, was the entire, long history of art.

It is understandable that given such a ‘synthetic’ approach, an insistence on one’s own individual ‘vision,’ on one’s own individual approach, would mean contradicting the fundamental rules of this system.

In actuality, in Koshelev’s studio, a number of students would work on one painting, and the works of the master himself could be completed by his ‘co-workers,’ as each who was in his class was called.

During these years Koshelev was exhibited in many exhibits both at home in his country and abroad.

Koshelev’s pedagogical work was interrupted by the closing of VKhUTEMAS. The artist, along with his family, moved to the city of Barnaul, which was connected with the artist’s childhood years. He died in 1934.

The fate of many of the master’s works continues to remain mysterious, and until the present time doesn’t allow us to answer many questions which directly involve his creativity. How and where could the main corpus of his works have disappeared (242 paintings alone were counted at the last of his personal exhibits in 1932; the Barnaul collection has 26 paintings and 18 graphics)? Which of these paintings were personally painted by Koshelev and which by his students and copyists (since 1936 numerous copies of Koshelev have appeared)? Where are the manuscripts, letters, the entire creative archive of the master? Soviet art history has yet to provide exhaustive answers to these questions.

CONCEPT OF THE INSTALLATION

The concept of this work, as it seems, is quite simple. A catastrophe, destruction, turns into construction, and contemplation with the sudden shift in point of view. Water, as the image of the all-destructive flood, self-propelling, turns into the image of a different flood – of the all-consuming element of music. The destruction of one artistic situation (the inability to ‘contemplate’ the works of art tranquilly and pensively) leads unexpectedly to the creation of a new, no less artistic, situation – the sudden appearance of a concert hall with ‘performers’ and ‘listeners.’ Everything receives its own ‘turn around,’ its reverse side.

The chance extraneous objects – buckets, jars – which don’t make sense and are unthinkable in a museum, form a well-organized ensemble of wonderful sounding instruments. Water is transformed from the tool of destruction to the main musical means. In its musical transformation, the water’s falling downward, like a sign of ruin, turns into a symbol of harmony that is escaping upward … But, of course, none of this could have happened, there wouldn’t be any Water Music, if three important conditions hadn’t been met.

This ‘transformation’ could occur only in the high, tense atmosphere of the museum space, where everything is like it is in a temple (and today’s museums are in fact such temples), which prepares the soul for an extraordinary elevated experience.

Inside of this space there turned out to be people who were capable of hearing such music, i.e., there are not very many of them who have this absolute internal musical ear, who were ready to make sense of this and who were able to renounce the impressions of the chaos reigning around them and hear the harmony of sounds that were suddenly ringing out. (But this couldn’t have occurred in a shelter under an awning where a chance passer-by took cover from the rain, although in principle, why couldn’t this happen there also?)

This attentive listener, capable of this sort of switching off of consciousness, had to have already wittingly possessed that reserve of cultural musical memory which would allow him to connect the sounds of water dripping into buckets with the ‘conversations of drops’ of marble chalices in Arabic palaces, with the splash of fountains and water cascades of French parks that are well calculated in a musical sense, and perhaps even with Handel’s Water Music.

In this entirely ‘fabricated’ installation, there is one element that was made ‘in all seriousness,’ composed without any joking whatsoever. That is the musical score, composed and arranged from the water sound by the composer Vladimir Tarasov. Having spent a long time balancing these sounds precisely and carefully, he created an entirely independent musical score. In the first, ‘red’ hall, it sounds lively, in major tones, creating a very active overall mood. And, what is most interesting, it develops spatially. The viewer-listener, moving from one group of ‘musical’ instruments to another, begins to hear a new ‘score,’ and the previous one, in correlation with his moving away from it, becomes a harmonious accompaniment to it. The listening to the music, hence, turns out to be connected with the movement throughout the entire space of the installation, and is organically connected with the viewing of all of its parts. In this way, the music can be heard in two ways: both in the immobile state of standing in one place, and while moving: the score is harmonized in all points of the space of the dwelling.

In the ‘small,’ ‘green’ hall of the installation, the water music carries a different, we might say, chamber quality, and there are fewer instruments here. Drops resound in various corners of the room at long intervals, the sound of the tiny droplets on the plastic provide soft, tense accompaniment, and the whole space is filled with ‘resounding silence’ – everything together creates an elevated, meditative mood.

This combination of the sound in the two halls, forte in the first and piano in the second, unites the entire installation in a musical sense into a single whole, creating for the viewer the impression of tension and release, build up and subsequent calming.

Images

Literature