We Are Leaving Here Forever

YEAR: 1991

CATALOGUE NUMBER: 54

PROVENANCE

Collection of the artist.

EXHIBITIONS

Carnegie International 1991, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

19 October 1991 – 16 February 1992.

Bilbao, Sala de Exposiciones de Rekalde

El Puente, 21 Nov 1995 — 21 Jan 1996

DESCRIPTION

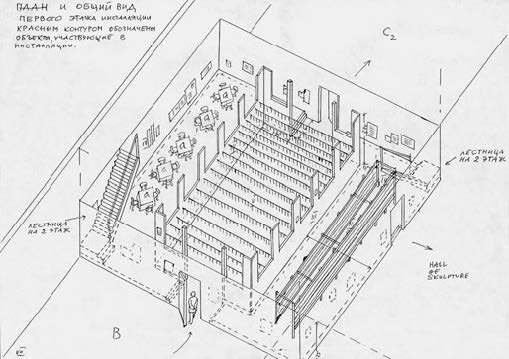

The dwelling C1 of the Carnegie Museum which has three doors – from Hall B, from Hall C2, and from the sculpture hall – was used for the installation. The two main doors of the installation, its entrance, and exit, are arranged along the main axis of the exhibit leading from Hall B to Halls C2 and C3. The installation is a two-story structure – a ‘building’ that surrounds the ‘courtyard’ on all four sides. The first floor of the building is raised 40 cm above the surface of the courtyard. The entire courtyard along the perimeter is surrounded by window apertures from which the viewer can look into the yard and watch what is going on there. Stairs are located to the right and left of the entrance doors, and by ascending them you can wind up in the two peripheral dwellings of the first floor. This is the ‘cafeteria’ where old chairs and tables are standing one after another covered with tablecloths, and on the table is a menu with a completely ‘special content’ of dishes; and here is the ‘library’ where all kinds of drawings, texts, sketches, postcards are glued on top of long strips of wallpaper that are nailed to three vertically standing wooden structures. In the left corner from the entrance, there are two sets of stairs leading to the second floor. The viewer winds up in a corridor, along which one may walk, not lingering, around the entire building, and through the window apertures, he can see the opposite windows and courtyard below. From the corridor one may enter each of six rooms (three on each side of the building), where there is also almost nothing, not counting the papers with texts and drawings hanging on the wall. The same kind of pages hang in various places in the corridor, on the stairwells; they lie in piles and individually on the floor. (It’s the same on the first floor.)

Now about the most important thing: about the center of the installation, about what is located in the courtyard, and about the objects hung there.

The ‘center’ consists of 16 ropes, tightly strung across the courtyard above the entire surface at a height of 155 cm, that is at eye-level for a person of average height. To each rope, at a distance of 30 cm from one another, some kinds of ‘garbage’ objects are tied on thin strings: an empty box, a lid to a jar, a crumpled old package, etc., and under each of them on a small paper label is a text. The texts – only two, three lines long – are fragments of utterances of children gathered together in the courtyard and anticipating their future. These texts are very tense, full of the most contradictory feelings – confusion, hopes, pain … There are as many such fragments – 320 – as there are objects. In this way, the entire courtyard turns out to be an extraordinarily electrified, dramatic space, a unique sea full of sorrow and anticipation.

Now about the two main characters of the installation: about light and the viewer.

The installation is envisioned in such a way that the viewer himself will bring the concept of the installation to realization with the help of light. The thing is that the light will be turned off (not counting the small electric bulbs above the stairs and in the corridors providing weak light, permitting one to get oriented in space). But on the whole, it is rather dark in the installation. There are little tables standing near all three doors, and on each is a small number of electric flashlights. The viewer takes a flashlight and sets off with it to investigate the mysterious dark space where he has wound up. Only an illuminated square of a door on the opposite side can be seen up ahead in the distance. All the rest of the space arises before us as a sea of wandering lights, migrating in various directions. These lights are from the flashlights of other viewers who have entered before us. Each person searches out an object in the courtyard, rooms, and corridors with his flashlight. The installation consists of a multitude of lights, wandering in space. Each viewer sees only one fragment which he has managed to illuminate. (Of course, we are all familiar with this gripping effect, we have all experienced it at least once in our lives: to wander alone with a flashlight in some mysterious, neglected, unfamiliar dwelling.)

With this, the viewer in motion creates the overall effect of the installation. Now it is clear why the floor of the first floor is raised 40 cm above the level of the courtyard: looking out of the windows, the viewer sees the space of the yard like a sea of lights below him.

Under the conditions of a group exhibit, the installation should, despite its own ‘sad’ content, nonetheless create the impression of a happy and funny attraction that always occurs when the viewer himself, involuntarily, winds up as a participant of some orchestrated ‘act.’

And finally, in order to enter into the other dwellings (C2 and C3), the viewer is not at all obligated to take a flashlight and proceed with it. He can move from one door to another, merely bending down slightly, or he can use the side dwellings running to the right and left of the ‘courtyard.’

CONCEPT OF THE INSTALLATION

1- On the surface level

The building housing the large children’s dormitory is closing forever. Many children have lived there, children of 12 to 15 years of age and older, children who have had no parents or regular family.

All the children have been gathered downstairs in the yard. In the next few minutes, they will leave forever the place where they have lived together for such a long time, some of them for many years. The entire two-story building stands empty and semi-dark: only a few dim lights burn weakly in the corridors and in the stairwells. There is no one in the library or in the dining hall or in the upstairs rooms. Everything of use has already been hauled away, except for the old tables and chairs in the dining hall. Yet it is impossible to say that the building is completely empty. Only those things that nobody has a use for any longer remain: a huge number of papers that have accumulated in the building over all these years. Papers cover the walls and floors of the abandoned building: innumerable announcements, instructions, rules for the use of the communal areas, slogans, exhortations, schedules … Many of these include pictures, caricatures. There are also letters, notes, diaries, bulletins …

Everyone gathered below is extremely agitated. Nobody knows what lies ahead. Many are sorry to leave the old building – nobody understands why it is necessary to give up everything so suddenly and depart for an unknown destination. Each child engages in private speculation and guess-work. An unimaginable noise from the multitude of voices reigns in the yard.

2- On the symbolic level

On this level the concept is entirely clear: in front of us are the final minutes before the human souls abandon ‘this’ world. The ‘lights’ are turned off, the world has lost its sense and colors; it is dreary, desolate. Nothing remains but a sea of useless papers, in which merciless orders, precise timetables, touching letters, and notes are all mixed together. Some recall the past and mourn for it. Almost all are full of terror before the imminent uncertainty that awaits them.

ARTIST`S COMMENTS

One of my most vivid and most terrible memories is of life in a school dormitory. But it is one of the most strangely pleasant, painfully touching at the same time. Both of these feelings comprise an excruciatingly sweet fusion in which I cannot distinguish one from the other: unbelievable, unimaginable anguish from the joy of solitary (strange as it may sound in reference to a dormitory) drawing in the corner, with my back leaning up against the warm radiator; the daily assault on us by the older kids, the turbulent trek to the cafeteria which was four blocks away from the school; the crazy game of soccer right in the street, among pedestrians and cars where a rock served as our ball; empty food jars, pieces of ice in the winter …

… I entered the dormitory of the art school in 1943 in Samarkand, where mama and I had been evacuated during the war. I was 10 years old at the time, and I lived there until 1951 when I moved to the dormitory at the Surikov Institute. There were 75 of us living in the dorm, which was located on the top floor of the school where ‘day’ students from ‘normal’ families also studied art. In the morning after breakfast we would go down to our classes where we would have 6-7 lessons in a row, and then in the evening, we would go back up to our own floor where we spent the remainder of the day and night. We almost never went out anywhere, if you don’t count the group treks two times a day to the cafeteria and once a week to the bathhouse. Our entire life was spent among people of our own age. Moreover, there existed the strictest subordination: a younger person submitted to a senior one unquestioningly, the elders were the ‘masters,’ the younger ones were the slaves, simply by virtue of their age. The younger ones were forced to clean up after their elders, cook for them, and often corporal punishment was organized in the evening: punishment of the younger kids for their offenses before the highest powers – the ‘elders’ (among whom many were genuine sadists). The management of the school, the director, didn’t get involved in the affairs of the boarding school: I now understand that the atmosphere reigning there suited them just fine. But how could it have been any different when the same thing was happening all over the country: these were the final years of the reign of the ‘Stalin,’ a time of the ‘approaching victory of Socialism throughout the entire world.’ ‘Ceremonial evenings’ were often held downstairs, on the first floor of the school where there was a sports hall. The very mention of the name ‘Stalin’ during these evenings would ignite tumultuous applause which couldn’t be stopped since all the bosses were afraid to be the first to stop clapping – this was fatally dangerous and could have (and did have) catastrophic consequences.

And so, it didn’t matter whether you were a ‘junior’ or a ‘senior,’ you were still always under everyone’s nose all the time, from morning until night. In the room, where only a bed and a nightstand belonged to you, there were 9-10 other beds, and the door was always open. The main part of life occurred in the corridor: couches and small tables stood along the walls, kids ran, sat, made noise, your ‘comrades’ fought with each other, everything happened in the corridor. There was nothing, as I remember, of ‘one’s own’: any one of your roommates could put on your coat, cap, boots by mistake or simply ‘just because.’

But on the other hand, there was so much that was pleasant, light, joyful! You weren’t responsible for anything. Everything around you was someone else’s, not yours. Food, clothing, the bed, textbooks – all of it was given to you, we didn’t pay for our studies. You didn’t have to make any decisions at all; we were always told what was waiting for us today or tomorrow, where we were supposed to go and what we were supposed to do. On both ordinary days and holidays, the rules of life in the dormitory and even gifts – none of it required our consent. We accepted everything as the way it should be, like little goats in a cattle-yard, not discussing or splitting hairs over whose cattle yard this was and who was its master.

But the entire country wasn’t asking these questions either. At that time it resembled our orphanage, reduced to complete slavery, speechlessness and joyful idiotic patriotism at rare moments.

Images

Literature