Before Supper

YEAR: 1988

CATALOGUE NUMBER: 14

PROVENANCE

The artist

1993Collection Museum Ludwig, Cologne

Museum Ludwig, Köln 1993

EXHIBITIONS

Graz

Vor dem Abendessen 20 Mar 1988 — 8 Apr 1988

(Organisation: Kunstverein Graz)

Venice

Aperto. 43. Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte. La Biennale di Venezia 25 Jun 1988 — 25 Sep 1988

Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum

Wanderlieder 8 Dec 1991 — 9 Feb 1992

Cologne, Josef- Haubrich-Kunsthalle

Von Malewitsch bis Kabakov – Russische Avantgarde im 20. Jahrhundert –Die Sammlung Ludwig 16 Oct 1993 — 2 Jan 1994

DESCRIPTION

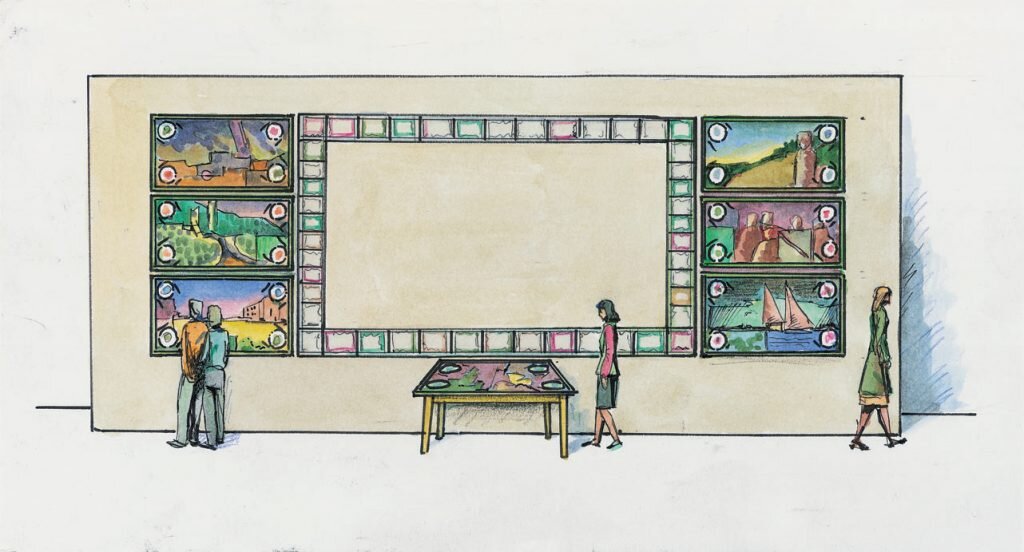

There is a large wall in front of the viewer that an is covered with smooth white enamel. There is an emptiness in the middle of the wall that is surrounded by a frame of 12 drawings (there is an empty space in the center of each drawing as well, with depictions only around the edges of the page). The drawings are done in colored pencil. There are three paintings hanging on each side of the ‘frame,’ one under the other, done in oil on canvas in the style of ‘Socialist Realism’ and depicting all possible banal subjects of our Soviet reality. Plates are attached to each of the four corners of the paintings, and next to them there are forks and knives, apparently for decorating the paintings. A seventh painting – the exact same kind as the others with plates and silverware – stands in front of the wall in the middle – with legs attached to it so that it looks like an ordinary table set for dinner.

ARTIST`S COMMENTS

There are people who have a specific talent: they are ultimately always able to create a successful general composition, no matter what they create it from. How, in what way? It’s difficult to say. They have two instincts: in the first place, they have a sense of the whole, the unified, interconnection, compatibility, balance; and in the second place, they have an instinct for the result, the end, completion.

But the combination of what, the formatted quality of what?

Why is this thing and not that one taken for a given work? And is the resulting whole connection with the meaning and content of that from which the whole is formed? Do these parts find their realization in the whole? Are they appropriate in it, in good taste? And what comprises the principle of the formation of the whole? What does ‘result,’ ‘end,’ mean? To whom is this result presented? Who is the viewer and who is the judge? Who (and for what reason) launched this mechanism forming of the whole, the unification of the parts, why is it necessary? And doesn’t the existence of things in the world serve merely as the grounds for these people to manifest their inherent instinct to combine everything with everything else? To what extent is the emerging whole correct in relation to its component parts? For, after all, it should ‘represent’ these parts. But perhaps it represents only itself, and requests that the parts be ignored?

I never had answers to all of these questions. But I must confess: the capabilities which I am speaking about were developed in me to the highest degree; that is, the organization of something and the receiving of some sort of overall result. But I repeat myself again: the organization of what? The result – what does it consist of and whom does it serve?

This interest in the whole and indifference toward the individual, the unitary; no desire to delve deeply into something, to investigate it thoroughly, but only ‘to enter it in the minutes’ and to present a prepared register as a result – doesn’t all of this amount to a dubious activity which no one needs, neither the person who writes it down nor the person for whom the list is intended?

Nevertheless, as long as I can remember, I have indulged myself in this endeavor all my life; I am occupied with it to this very day. What is this special ‘metaphysical’ book-keeping and who is the accountant conducting it?

…Not to enter into anything concretely, not to make a choice; to record everything, to number, to tie together into files, then to demonstrate that the work has been done, to take count once again, once again to file. Then once again to demonstrate…

Is it possible that this is an ordinary, unconcealed thirst for power? In listing the most heterogeneous, dissimilar objects, separating them by commas – horses, paintings, plates, food, and the like – don’t you remove from them their uniqueness, specialness, in essence their own individual life, leaving only the shell, the name, comprising from these shells a new whole according to your own arbitrariness? Acting in such a way, don’t you function like an ordinary agent of a totalitarian system, denying these creatures a right to an independent life, imparting to them your own order and your own organization?

And what about the result itself, the end of this ‘accounting’ works? Do you really present it to the Main Judge? Or only to yourself, satisfied with the consciousness of your own power and not mentioning even a word about the things that were used by you and which have fallen silent forever?

Images

Literature