Illustrations for a Bible

YEAR: 1991

CATALOGUE NUMBER: 39

PROVENANCE

The artist

1991, Collection Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt am Main

NOTES

See No 42.

EXHIBITIONS

Frankfurt am Main, Dominikanerkloster

Bilder zur Bibel heute, 29 Jan 1991 — 20 Feb 1991 (Organisation: Frankfurter Bibelgesellschaft, Frankfurt am Main)

Iserlohn

Bilder Zur Bibel Heute, 8 Mar 1991 — 16 Apr 1991

Bochum

Bilder Zur Bibel Heute, 24 Apr 1991 — 18 May 1991

Frankfurt am Main, Museum für Moderne Kunst

Szenenwechsel viii 23, Jun 1995 — 14 Jan 1996

DESCRIPTION

The installation consists of a plywood screen in a wooden frame hanging on the wall. Six typewritten pages of text are affixed to the screen, and underneath them, there are color copies of drawings and sketches. All of this taken together resembles some dreary bureaucratic object that is familiar to all and that has grown tiresome and that has nothing ‘artistic’ about it, neither in appearance nor in the way it was painted.

So why does this bureaucratic product carry the proud title of ‘installation?’ Because, like any installation, it is connected with the environment, the atmosphere where it hangs and ‘lives’ and it is an organic part of this ‘atmosphere.’ I requested that this stand be hung not in an exhibition hall, but rather in the corridor of the ‘private’ part of the museum where official papers hang and where this stand could ‘get lost’ amidst similar joyless products and so that it wouldn’t occur to anyone that this was an ‘artistic’ work hanging before them.

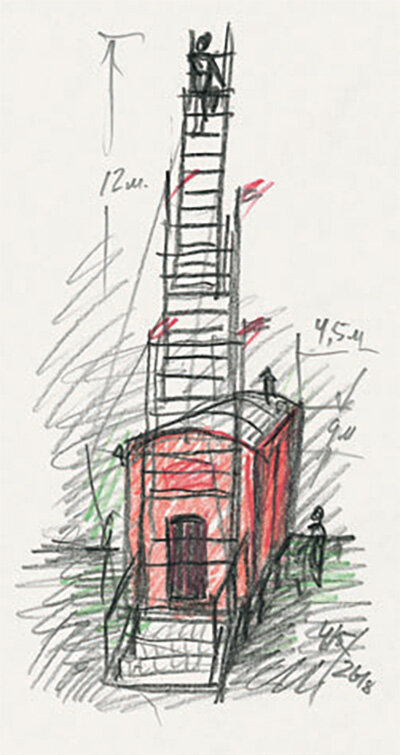

The Red Wagon

The installation consists of three parts which constitute a unified whole with a length of 17 meters, a width of 3.5 meters, and a height of 7 meters. The first part, which comprises the beginning of the viewing and at the same time the entrance into the installation, consists of a wooden construction made in the ‘constructivist’ style of the 1920’s. It is an intricately built staircase leading upward and purportedly into space, into the sky. It represents movement toward a wonderful future. At the very top of the stairs are a lot of flags, pennants, slogans – festivity rules there in the sky.

Adjoining this structure from behind is a ‘red train-car’ – long (9 meters) and wooden. The box, which looks like a train-car, is painted ‘train-car’ red-brown, and it stands on low wooden supports instead of on wheels. Sixteen paintings in the Socialist Realist style are hung along both sides of the car in place of windows. Having stepped inside, the viewer winds up in a rather dark place. Stretching the entire length of the wagon on the left is a two-leveled bench inviting the viewer to sit down. The right side of the wagon appears to be a long stage where it seems that the action will begin any minute behind a wooden barrier. On the stage as a backdrop is a large painting depicting the plans for the ‘wonderful city of the future’: straight roads, buildings, green parks, dirigibles in the air. Rather loud music from the 1930’s and 1940’s resounds that is either lively or lyrical, full of energy. Behind the car is a small step but with broken railings. In general, beyond the car, terrible chaos and disorder reign, big piles of junk and garbage are heaped up: ripped up packaging, boards, boxes, empty crates; everything that is left over after the building and painting of the first two parts of the installation – the ‘stairs’ and the ‘train-car.’ It is everything, apparently, that should have been cleaned up and swept away, but either they didn’t have enough time, or they’ll take it away later, or else they simply forgot. It’s not clear, but this garbage comprises the third, also important, part of the installation.

Around 1985, because of some sort of peculiar drop in energy in our country, I and many of my friends felt that some important period of Soviet history had ended. Some sort of new, already ‘non-historical’ time had begun. But for me, it was clearly felt also that not only a particular period but all of it, of this ‘Soviet history’ which had begun in October 1917 ended with this year (1985) – it had ended and would never return. That which it seemed would last for an eternity had quietly burst and leaked out, like an old painful, purulent boil.

And it was infinitely important to understand this ‘Soviet time’ from its beginning to its end and in some way to reflect, to describe, ‘to engrave’ it, so to speak, so that never again, neither before nor after should anything similar ever be repeated in human history. But how, in what way should this Soviet history be presented visually in its integral development? In my imagination, it is in the form of some sort of arch, some kind of ‘bridge.’ Its first period – the time still full of faith and enthusiasm, hopes for building a bright, wonderful future – appears to me like the initial part of a bridge leading upward. In time this is the period from October 1917 until 1932, the year of the Congress of the ‘Victors’ who were then almost virtually all shot by Stalin.

The second period is that which followed this one – the period of the ‘eternal Soviet Stalinist Paradise,’ when the far-off future moved closer in an instant and became the eternal, wonderful ‘now’ – time stood still just like it is supposed to in Paradise, and everything bloomed eternal so that it would never fade away under the sun of Stalin’s constitution and his unsleeping eye. This is the time from 1932 until 1963, and it can be imagined as the middle of the ‘bridge,’ it’s even, horizontal part. Finally, the third Soviet period from 1963 until 1985, when everything, as though moving down off of the bridge, moves toward its inevitable end. This is the ‘Brezhnev’ period, a time of accelerating internal collapse, a period during which one after another of those four powerful pillars were destroyed – its ideology, economy, foreign politics, and military strength – the pillars which, it seemed, had supported the ‘great, powerful Soviet Union’ which had been built for eternity. The consciousness of our generation got to witness the still ‘triumphant’ second period, and completely live through the entire period of decline and destruction, to glance from the ‘end to the beginning’ of that horrible fairytale which had taken place not in the imaginary world of fantasy, but in reality.

But we can see just as clearly (and most of all thanks to the book by Boris Groys, The Total Art of Stalinism) that these three periods coincide with three important stages of development of graphic art in our country: the period of avant-gardism, the Golden Age of Socialist Realism, and the period of unofficial art (Sots Art and others). Many think that these three periods are in opposition and exclusive, but actually, they altogether represent a unified, connected whole. Hence, readily suggested is the depiction of ‘Soviet history’ as this ‘bridge,’ as a special combination, or joining, of these three artistic systems in which what distinguishes one from another can be distinctly seen.

But for the creation of a clear and unified image, this device looks too visual, extraordinarily illustrative. A more intricately revised solution was required, where all three of these parts of the ‘bridge of art’ would be included in a more subtle fashion and would form a new whole.

The installation The Red Wagon appears to me to be such a solution. It is the depiction of the path along which the viewer must pass, so to speak, having felt physically the beginning, the middle and the end. Having experienced the impossibility of being able to ascend the stairs into the sky, and then having experienced the heavy boredom of ‘eternal anticipation,’ he winds up amidst a pile of dirt, debris, and insignificant rubbish.

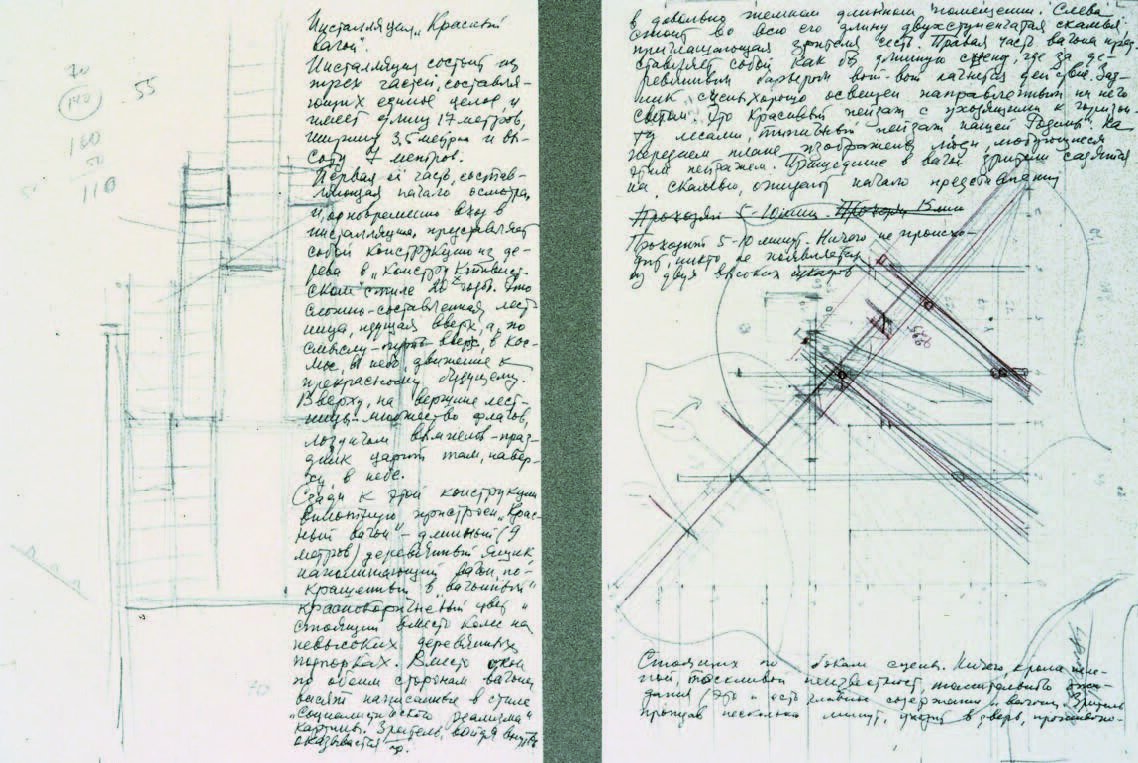

… Toward the middle of September, all the technical plans for the construction of the installation were almost ready, and then, while sorting through a heap of papers and sketches on my desk, trying to find one drawing lost among them, I suddenly saw the letter from Frankfurt. It was as though I were doused with flames: this installation was in fact based on a theme from the Bible! And not just one theme, but two such themes were distinctly and clearly realized in The Red Wagon: the story of Jacob’s ladder, and the story of Jonah trapped in the belly of the whale. Aren’t the utopian towers and constructions leading up to the sky, the projects of the Russian Constructivists from Tatlin to Vesnin (whose image is repeated in the stairs of The Red Wagon) just modern variations of Jacob’s ladder? And couldn’t The Red Wagon itself, with its underlying images of gloomy prison camp barracks or a poorly lit communal apartment in our Stalinist ‘paradise,’ be understood as the enormous inside of a whale that the unfortunate Jonah found himself trapped in?

It suddenly seemed to me that I couldn’t conceive of a better illustration of a theme from the Bible. Furthermore, the whole story with The Red Wagon demonstrates in the best possible way just what role the Bible plays during our time! Briefly, the following could be said: it is impossible today to think up and make a single sufficiently large and compact image that in its very depths, in its original conception, doesn’t rest on some biblical theme. At the bottom of our artistic memory lie themes, networks and problems of the Great Book. You cannot escape this. Its themes may be selected entirely consciously, re-reading its pages with open eyes during the light of day, so to speak, or they could turn out to be hidden and encoded deep in the subconscious, bursting suddenly and unexpectedly to the surface of consciousness, as in my case.

But the invitation to the exhibit turned out to be unfulfilled. Paintings were not painted, and there was nothing to exhibit.

But what is the point of ‘conceptualism’ then? Was it really invented not specifically for such instances?

… And so, I had to quickly grab some sketches and glue them to gray paper, along with some explanatory text. These pages were to be arranged at the exhibit in two rows (as indicated in the diagram).

And the viewer, experienced in the ways of contemporary conceptual art, would quickly evaluate this ‘subtle concept’ of an illustration for the Bible even if he didn’t quite believe in the whole story about The Red Wagon.

It would be interesting to know: is there a story in the Bible that corresponds to this extremely witty resolution?

Images

Literature