Monument to a Lost Civilization

with Emilia Kabakov

YEAR: 1999

CATALOG NUMBER: 141

PROVENANCE

Collection of the artist

NOTES

Consisting of the No 6, 9, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 30, 31, 36, 48, 50, 51, 53, 56, 66, 67, 72, 75, 76, 83, 86, 90, 99, 100, 102, 107, 109, 114, 115, 126, 139,The Man Who Saved Nikolai Viktorovich,The Man Who Collected the Opinions of Others as well as two projects from The Palace of Projects: Man-Angel and A Universal System of Depicting Everything. Also consist of No 162, “A Universal System for Depicting Everything,” and No 168, “Let’s Go Girls.”

EXHIBITIONS

Palermo, Italy

Ilya e Emilia Kabakov. Monumento alla civilità perduta. Monument to a Lost Civilization, 16 Apr 1999 — 27 Jun 1999

Adelaide, University of South Australia Art Museum

Telstra Adelaide Festival of Arts 2000, 3 Mar 2000 — 26 Mar 2000

Sydney, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Museum of Contemporary Art

The 12th Biennale of Sydney, 26 May 2000 — 30 Jul 2000

Christchurch, COCA – Center of Contemporary Art,

Art and Industry, 20 Sep 2000 — 31 Dec 2000

Hamburg Kunsthalle, Hamburg, Germany

Das Gedächtnis der Kunst. Geschichte und Erinnerung in der Kunst der Gegenwart, 16 Dec 2000 — 18 Mar 2001

A Collaboration between the Schirn Kunsthalle, the Historisches Museum, and the Paulskirche, Frankfurt am Main. Installation by Ilya and Emilia Kabakov in the Schirn Kunsthalle.

Kunsthalle Göppingen, Germany

Ilya Kabakov: Universal System Zur Darstellung von allem / A Universal System for Depicting Everything, February 10 to March 31, 2002

Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Traumfabrik Kommunismus: Die Visuelle Kultur der Stalinzeit / Dream Factory Communism: The Visual Culture of the Stalin Era, September 24, 2003 to January 4, 2004

Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, Netherlands

Lissitzky – Kabakov: Utopie en Werkelijkheid / Lissitzky – Kabakov: Utopia and Reality, December 1, 2012, to April 1, 2013 (elements of the installation slightly modified)

DESCRIPTION

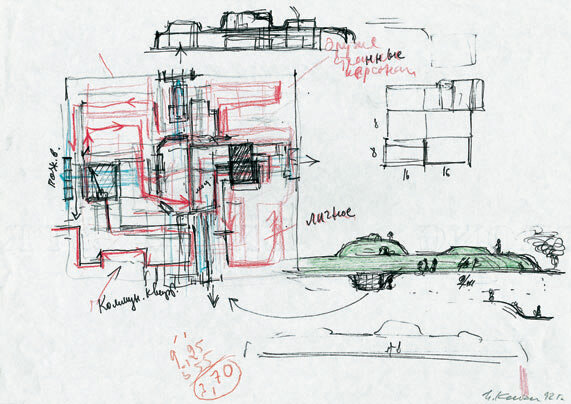

The ‘memorial’ represents a complex of 38 ‘total’ installations and forms a gigantic total installation 60 x 80 meters in size with a height from 3.5 meters to the highest point of 7 meters. One side of the ‘Memorial’ abuts the art museum in a large city and is located on a lower level than the rest of the museum halls. There is no special entrance into the installation, and the viewer enters it simply from one of the halls of this museum, winding up in its world as though entirely accidentally, merely following the signs ‘To the Summer Garden.’ But here, instead of bright classical museum halls, he suddenly discovers an entirely different civilization living according to entirely different laws. But this world, so unusual and strange, itself consists of two ‘spaces,’ one inserted into the other, that are sharply opposite to one another in meaning. The first space is the interior of some enormous, pompous but unfinished structure. There is scaffolding in places, construction materials lying around. Before us is the ground floor of a part or the side wing of a gigantic building, possibly the ‘Palace of Congresses,’ conceived of in the majestic form of Stalinist architecture with its massive square columns and high ceiling with gold cornices. But all of this unfinished magnificence is inserted into another very different place, a different architectural world. This magnificent, grand architecture has been reworked for a completely different space, adapted for entirely different goals. Just as is the case when new temporary pavilions are built into old classical palaces, here too, everywhere are new, quickly assembled and hurriedly painted walls forming new large and small spaces, alleys, corridors with lots of doors. The viewer, having wound up here, moves along a specific route, following small signs placed everywhere that say ‘To the Summer Garden,’ which lead him through this entire gigantic labyrinth, from corridor to corridor, from hall to hall, to the last room (but not to the ‘summer garden,’ since the sign on the door to it reads ‘Closed. No Entrance’). Then the viewer returns to the museum from where he came, only along a much shorter and straighter route. Each of these spaces – the halls and the corridors – are separate, independent installations with their own self-contained plots. All the plots of the installation are connected to one another and form a unified, connected whole from beginning to end, similar to a play having different acts. But here, the connection of these ‘acts’ is not temporal, but spatial.

The Structure of the ‘Monument’

The entire project consists of a complex of 38 installations forming seven different ‘sections’ separated from one another by corridors. You can walk from one ‘section’ to another along these corridors, like along streets of a small town. Each such ‘section’ is dedicated to a special theme. Let’s move on to a description of each of them.

1st Section (A): ‘Area of Communist Ideology and Propaganda’

Four installations are located in this area in a suite of central halls running along a single axis:

The Red Corner (No 83)

We Are Living Here (No 86)

The Bridge (No 53)

NOMA or the Moscow Conceptual Circle (No 76)

The first three installations represent ‘official’ ideological structures, whereas the last one, NOMA, represents ‘unofficial,’ underground artistic life. The installation We Live Here occupies a special place in this area. It is the center not only of this ‘section,’ but also of the entire ‘Memorial’ as a whole. This installation, therefore, is much higher than the other spaces of the memorial. The general ‘air’ of these three halls is pompous and solemn.

2nd Section (C): ‘Communal Life’

In this ‘section,’ directly across from the entrance, the most characteristic form of Soviet reality – the ‘communal apartment,’ is displayed, where more than 85% of the urban population lived during Soviet times. In each of the rooms of such an apartment live individual ‘residents’ with their own phobias, fantasies, and means for fleeing or hiding from the surrounding world. In the middle is the main knot and center of all problems – the communal kitchen. The following installations participate in this area:

Man-Angel1

In the Closet (No 115)

Toilet in the Corner (No 51)

A Universal System2

The Collector (No 20)

The Composer (No 19)

The Man Who Flew into His Painting (No 16)

The Man Who Flew into Space from his Apartment (No 9)

The Short Man (No 18)

The Man Who Collected the Opinions of Others (Part of Ten Characters)

The Untalented Artist (No 17)

The Man Who Saved Nikolai Viktorovich (Part of Ten Characters)

The Communal Kitchen (No 48)

Obviously, the ‘atmosphere’ of this area is sad and sorrowful.

3rd Section (B): ‘The Bureaucratic World’

Represented here is the situation of interminable inventory, certificates, explanations, appeals – a sea of paper and information about the personal, official, social, any aspect of life of a Soviet person. There is only one installation here:

The Big Archive (No 66) but it concentrates all of the problems. The installation is arranged to the left of the entrance.

4th Section (E): ‘Museum and Educational Zone’ Here belong: the museum hall, the reading room, the library, and other places of ‘cultural’ pastime:

He Went Crazy, Undressed and Ran Away Naked (No 30)

The Reading Room (No 90)

20 Ways to Get an Apple, Listening to the Music of Mozart (No 109)

A Solemn Painting (No 26)

The Empty Museum (No 67)

Three Nights (No 23)

Ten Albums (No 6)

The Artist’s Library (No 99)

5th Section (D): ‘The Hospital and Scientific Research’

Here is a ‘complex’ of a few ‘treatment’ establishments, as well as research on the life of a ‘fly’ civilization located in the atmosphere over the territory of Russia.

The Mental Institution or the Institute of Creative Research (No 50)

Healing with Paintings (No 102)

Treatment with Memories (No 107)

Psychological Confessions3

The Children’s Hospital (No 139)

The Life of Flies (No 56)

6th Section (F): ‘The World of the Memory’

Here are clustered installations devoted to the biography and personal memories either of people close to the author or of the author himself, or the memory of invented and created personages:

The Boat of My Life (No 72)

Labyrinth. My Mother’s Album (No 31)

The Man Who Never Threw Anything Away (The Garbage Man) (No 21)

Mother and Son (No 36)

7th Section (G): ‘Childhood Monuments’

These installations are located in the far right corner from the entrance. The general concept of this area is the childhood images that have remained in memory, perhaps the “ruins” of childhood: memories of life ‘in the attic and on the roof’ and of ‘school.’

On the Roof (No 100)

Deserted School or School # 6 (No 75)

The last installation tells about an abandoned school where no one studies anymore.

About the Subjectiveness of the ‘Monument’

The entire project looks like a depiction of ‘Soviet civilization’ that is now bygone but that did actually exist. Consequently, it presumes to depict diverse aspects of that civilization: ideological, everyday, social, etc. But this project should not be considered ethnography, wanting to precisely and realistically recreate the actual details (similar to a new museum of the type ‘The Life of Ancient Egypt’ or ‘The World of Icons,’ etc.) of life in Russia between 1917 and 1990 when Soviet civilization suddenly evaporated into thin air, as though it never existed before. This did not enter into the author’s task at all, and this would be beyond the scope of one person. The entire project represents merely the sum of subjective images, almost fantasies, of a person who lived in this world, but who saw everything through the prism of his inner vision and not from the perspective of an outside and objective observer. The author is simultaneously both a victim and an observer, a doctor and a patient, the subject and the recorder.

Therefore, for the viewer who enters these installations, it will turn out to be possible to see and feel, so to speak, ‘from inside’ this entire ‘atmosphere,’ this entire ‘aura’ of this bygone life as expressed by a witness to and participant in it, and not resulting from later archeology attempting to recreate a world that has disappeared. Obviously, the latter is virtually unattainable. Although you could display objects of everyday reality, even wonderful artistic works, you would not be able to recreate the ‘air’ between them. Everything would transform into depressing ‘Halls of Scythian Culture’ that no one would go see. It is only a ‘world of installations’ as created by the author himself that contains this atmosphere in the spaces of the proposed project, thereby allowing a visitor wandering around inside this world to feel it. The author sees the historical uniqueness of such a project precisely in this rare opportunity.

The External Appearance of the ‘Memorial’

The idea of arranging such a project ‘underground’ is dictated by conceptual, as well as material and practical considerations. Conceptually, the author sees the Soviet world as an underground world, located not in the plane of normal, democratic life of other people, but rather as an intermediary world, as a certain ‘purgatory,’ as a world of strange, agonizing, almost irrational existence, existence that is almost bewitched, living under the influence of some sort of ‘magic’ – and this is how it was in reality. Therefore, the actual location of such a memorial, naturally, is underground, down below, under the ‘normal’ life of people.

The ideal location of the project is in the basement of the museum, but knowing that vaults and workshops are usually housed downstairs in any museum, this appears to be unrealistic. Therefore, the project foresees an underground location next to the museum, so that you can descend into it via 3-4 steps from one of the museum halls. But in order not to waste the city space above, there you could design a square with trees and benches, make a sort of ‘roof’ in the city park. Such ‘practicality’ would intensify even more the conceptuality of the main idea, it would make it clear and obvious: down below is a semi-dark, mysterious, irrational world without windows; up above is the sun, trees, air – a free world of free people.

CONCEPT OF THE INSTALLATION

The Russian Revolution, ushering in the ‘era of Socialism,’ is considered to be an extremely important event of the 20th Century. The end of this ‘era of Socialism’ during the end of the 1980’s could be considered a no less important event of our century. But totalitarianism exiting the political arena in Eastern Europe and the territory of the former Soviet Union does not signify merely that a viscous and heavy fog has suddenly dissipated into thin air and underneath the shining, cloudless ground of democracy has been revealed once again. Totalitarianism is still preserved in the consciousness and subconscious of people who survived it and experienced its influence personally. However, it is equally clear that totalitarianism did not simply fall upon humanity as a political system from nowhere, but rather its ‘seeds’ live and exist in each of us, and, for the sake of the future, this cannot be forgotten or ignored.

This is why the creation of a unique memorial to Soviet totalitarianism is so important. However, this will be a memorial not to its victims who perished in the camps – that memorial has yet to be created and erected on the very territory where all of that occurred. Instead, this will be a memorial to those who survived in that world, but with a consciousness deformed under the influence of propaganda and incessant mental repression, which in extreme forms led to the emergence of the consciousness of the ‘Soviet person’ with his false enthusiasm and double-mind. This is a memorial to Soviet life in its everydayness, in its ordinary ‘daily existence,’ where, in particular, the natural connections of a person with the world, with others, with his own soul, were violated in every trifle, influenced by all-pervasive fear. This is a memorial to the various forms of survival of ‘the humane in an individual’ – this survival at times took the form of strange, hideous, fantastic, and at other times funny and endearing projects that a person juxtaposed to the most ‘beautiful’ and bloodiest project in the history of humanity, i.e. the creation of Communist Paradise on this Earth.

But after all, this relates to any person in any society, not only in a totalitarian one, where society in any form deforms the human personality, forcing him to subordinate and change his own human nature.

Images

Literature