The Old Reading Room

with Emilia Kabakov

YEAR: 1999

CATALOG NUMBER: 143

PROVENANCE

The artist

Not preserved

EXHIBITIONS

Universiteit van Amsterdam, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Doelenzaal, Amsterdam

The Old Reading Room, 8 Jul 1999 — 6 Aug 1999

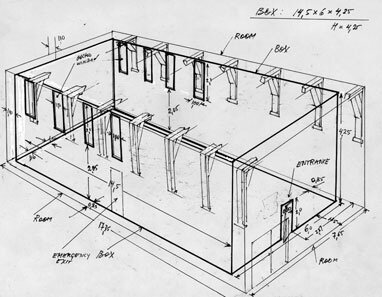

CONCEPT AND DESCRIPTION OF THE INSTALLATION

In a large square space stand a number of old and not-so-old display cases, barrister book cabinets with glass doors, bookshelves with glass doors. They contain an enormous quantity of old books, some of them open for display, others simply standing in a row. In each case and on each shelf there are also priceless examples of printed and manuscript art. We can see hand-colored illustrations, golden letters, and ornamentation glistening on the bindings which have darkened with time. But the tightly closed cabinets and display cases occupy the space in total disorder, creating the impression that they were delivered here accidentally, placed here in the center of the room only temporarily. And, in fact, visually this place looks like a place of ‘exile’ for all these things. It is painted gray and resembles a sad basement or barracks forgotten by everyone.

But the character of the whole exhibition is not so much sad and forlorn as it is tense and dramatic. Eight windows, four on each side of the wall opposite the entrance, are brightly lit from the ‘street,’ and the strong ‘rays’ penetrate the darkness of the huge space.

But there are two elements, two active ‘figures,’ that create the main tension in this installation: long white curtains on the windows that are fluttering from the wind, on which light from the street flickers, and the dramatic, intense music filling the hall. These fluttering and flickering curtains and the music represent, so to speak, active and menacing ‘forces’ which hang below the ceiling of this room in the form of a constant and dramatic threat. These two worlds, these two levels – the world of books and the library below that is dislocated from its place, and the world of the wind, of the disturbing sound underneath the ceiling – create the dramatic, and at the same time the visual image of the entire concept.

What is going in here and what is the concept? The answer is provided on the external wall of the installation, in the text hanging over the door through which the viewer enters the hall. ‘Is it possible that the computer has really conquered everything?’

This problem is far from simple, especially in the humanities, where the computer has become not only a vehicle for obtaining quick and varied ‘information,’ but it now pretends to be something much more than that, replacing things that are most likely irreplaceable. In this particular case, we are talking about spaces such as the theater, museum, and library. But first and foremost, the library and this subject – the library and the computer – can be the subject of the most heated and intense discussions.

On the other hand, there is an enormous advantage to creating a universal net of information which can be ‘retrieved’ instantaneously onto the blue screen. This process is going to progress with phenomenal speed and, in general, the whole printed and manuscript archive of humanity can be ‘transferred,’ ‘transposed,’ into the Internet, and it is naïve and useless to protest against the ‘winds of history.’ But we are discussing something else here.

The image of a painting, in color on a computer screen, even presented in enlarged fragments, cannot replace the actual contact with the original, and it will remain merely information, more or less limited. A similar question is put to us here, where we must ask ourselves: can the image of a page of a book on a computer screen replace the book itself? And can the reading of this page on the screen at home replace our visit and the time we spend in the reading room of a university or any other public library?

Here we come to the main issue: the process of reading and our relationship with the book consists not only in getting information from the text of any particular book, but also in the intense context, the unique cultural and spiritual ‘aura,’ in which this book along with the reader are immersed. This special atmosphere is tangible in ‘traditional’ reading rooms that were created specifically for this purpose. In such rooms, where the atmosphere consists of the books, paintings, bookshelves and bookcases surrounding the viewer – in an architectural space created intentionally for producing this atmosphere – what occurs is a special concentration of this cultural ‘field.’ The viewer, at the very moment he reads the book, is absorbing not only the text and the meaning of this particular book, but he is connecting with the whole world of culture, embodying a part of this culture. The reader is a living and active participant in it. But this is true only if the library itself maintains this atmosphere. Unfortunately, many of them are changing very fast, being transformed into office-like spaces, where symmetrical rows of computers stand proudly on empty tables amidst empty walls.

But isn’t this vital world of culture here being replaced by simple, albeit varied, information about this culture, becoming (in ‘geometrical language’) instead of a three-dimensional space, just a flat, two-dimensional world?

The installation exhibited here is housed in a university library; perhaps it may, therefore, become a participant in this discussion.

Images

Literature