Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, Tate Modern review – funny, moving and revelatory

Not Everyone Will Be Taken into the Future: the artist who came in from the cold and met his soulmate

October 18th, 2017

by Sarah Kent

NOT EVERYONE WILL BE TAKEN INTO THE FUTURE - MAK AUSTRIAN MUSEUM OF APPLIED ARTS/ CONTEMPORARY ART

The Kabakovs’ exhibition made me thank my lucky stars I was not born in the Soviet Union. A recurring theme of their work is the desire to escape – from the hunger and poverty caused by incompetence and poor planning, and the doublethink required to survive under a regime that became ever more repressive the greater and more obvious its failings.

I first came across the Kabakovs’ work in 1992 at Documenta art fair in Germany. A concrete bunker with two entrances labeled “Male” and “Female” contained two rooms lined with latrines. Someone had filled these dismal spaces with furniture that included a crib and playpen. A homeless mother had apparently taken up residence in a public lavatory.

Their Tate Modern exhibition includes a model of this disturbing work and at the heart of the show is an earlier, similarly moving installation. Labyrinth (My Mother’s Album), 1990, is the only overtly autobiographical work made by Ilya Kabakov. A drab, poorly lit corridor is painted chocolate brown and dirty white, the colors of the communal living quarters in which many Muscovite families were forced to live cheek by jowl.

Along one wall hangs a sequence of picture frames each containing a pleasantly innocuous photograph of a park, garden or leafy boulevard taken by Ilya’s uncle, a professional photographer. Beneath each photo is a paragraph of text recounting the life story of Ilya’s mother, who had ambitions to become a doctor but ended up a skivvy. They detail the harsh realities faced by citizens in the new Soviet republic, whose experience was so far removed from the life of ease portrayed in the photographs. Emanating from a dusty cupboard at the center of the labyrinth is the melancholy sound of Ilya’s voice singing sentimental Russian songs that alleviate the misery. There’s no light at the end of this dreary and seemingly endless tunnel, though; the story has no happy ending.

Installations like these, which have brought the Kabakovs international fame, were made after 1987 when Ilya was finally able to leave Russia and move to the United States where he met Emilia, his future wife and collaborator. The exhibition starts, though, at the beginning of his career. Having studied at the Moscow School of Art, he chose not to become an official artist destined to churn out propaganda pictures in the Social Realist style. Instead, he illustrated children’s books while continuing to make work in secret, which he showed only to a few trusted friends.

In 1970 he began a delightful series of portfolios whose words and pictures are laced with bitingly mordant wit reminiscent of Franz Kafka. To escape the grinding tedium of daily life, 10 fictional characters adopt strategies which are portrayed in pictures filled with references to the kind of art banned by the regime. For Agonising Surikov everything is hidden from view by a shroud; cue for an exquisite series of drawings of shrouds resembling abstract expressionist paintings, through which reality is glimpsed via small holes.

The young boy, Primakov, withdraws into a dark closet. Labelled “mother is sewing”, “Olya is doing homework” and so on, the view from his hiding place is portrayed in a series of scribbled black rectangles – an ironic nod to Kasimir Malevich’s iconic painting of a black square. In the enveloping darkness, the boy recalls items such as a fresh tomato or carrot in words rather than images and Kabakov’s beautiful calligraphy anticipates the work of conceptualists like Joseph Kosuth and artists who use neon. Yet the boy retains a clear mental picture of the sky and ether, into which he finally disappears.

The Man Who Flew into Space From His Apartment, 1985 transforms the idea of ascension into a comic form of material reality. The only installation to be created by Kabakov in his Moscow studio, it shows a tiny bedsit lined with Soviet posters. A home-made catapult hangs beneath a large hole made when the occupant blasted through the ceiling to freedom leaving behind his shoes and the insistent clamour of propaganda.

Two themes surface in Ten Characters: the role of the imagination in providing hope and solace, and the ability of images to conceal or distort the truth. Alongside the portfolio Kabakov was making cack-handed paintings and reliefs which use words and actual objects to stress the need to interrogate images rather than take them at face value. A coat-hanger, nail and toy steam engine are attached to the surface of The Answers of an Experimental Group, 1970. In the accompanying text, fictional viewers interpret the objects as “the remains of some sort of psychological event” or “symbols: a threat”.

Throughout his career, Kabakov has repeatedly returned to the vexed issue of Socialist Realism, designed to prop up a totalitarian regime by propagating lies and euphemisms. Holiday, 1987 is a series of pictures supposedly commissioned from an official artist. Four cheesy depictions of leisure time have been defaced by a grid of sweet wrappers, as though another layer of confection might make the saccharine content more palatable. What use are mediocre pictures like these, Kabakov seems to ask. Not Everyone Will Be Taken into the Future, the installation which gives the exhibition its name (main picture), shows a train leaving behind a pile of unwanted canvases, as it heads into the future.

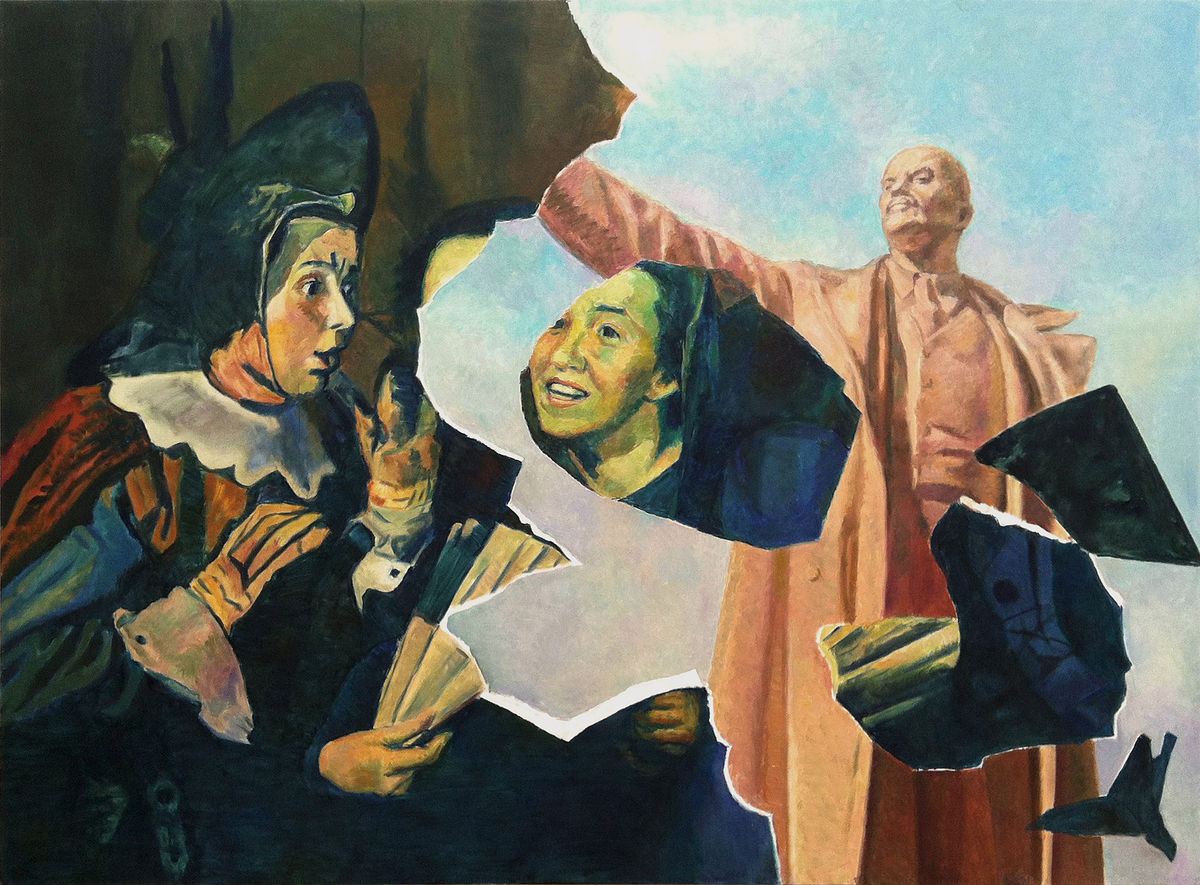

If Socialist Realism is a deceit, wherein lies the truth? In Two Times, 2015, fragments apparently torn from Social Realist paintings lie scattered across the surface of old masters so that smiling peasants rub shoulders with angels and schoolchildren encounter the naked Venus carousing with Pan in a Baroque masterpiece. In The Appearance of the Collage, 2012 (pictured above) Lenin seems to address a huddle of 17th century Dutch women. No image takes precedence; it is up to the viewer to choose between conflicting versions of reality, but as one member of the Experimental Group concludes “I don’t understand anything.” In the end, the laugh is always on us.