Artist Ilya Kabakov has breakfast at 7 a.m. every day. Emilia, his wife, a former world-class pianist, wakes up at 5 a.m. if she sleeps at all. She prepares her husband’s food in a kitchen with 20-foot-high wood-beam vaulted ceilings. Birds eat from metal feeders hanging from oak trees in the front yard. The soft waves of Peconic Bay sway against the shore down the hill.

Read MoreNos asomamos a uno de los momentos de más honda intensidad de la historia del arte del siglo XX a través de una exposición que está despertando un enorme interés en Europa. Se trata de ‘Utopía y realidad’, en el Van Abbemuseum de Eindhoven en torno a la relación entre dos gigantes rusos: El Lissitzky e Ilya y Emilia Kabakov.

Read MoreThe glare is almost blinding as the midday sun bounces off the snow, packed thick on the ground. Deer tracks make a delicate outline around the large, shingled house, which sits on a cliff on Long Island’s North Fork. Inside, lunch is waiting and Ilya Kabakov pads into the kitchen from his studio in paintspattered clothes. He and his wife Emilia eat, sleep and wake according to a strict schedule. “It’s a very organised household,” Emilia says as she dishes up a beef and vegetable soup. “It’s much easier to work this way.”

Read MoreYou are cordially invited to an evening with Emilia Kabakov, a part of the artistic duo, Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, the Russian-born, American-based artists, whose milestone exhibition opens at Tate Modern this autumn. Ilya and Emilia Kabakov are amongst the most celebrated artists of their generation, leading representatives of Moscow conceptualism and pioneers of installation art. Emilia will be in conversation with Achim Borchardt-Hume, Director of Exhibitions at Tate Modern in London.

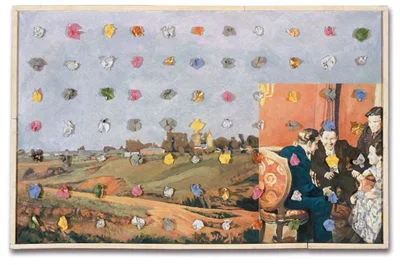

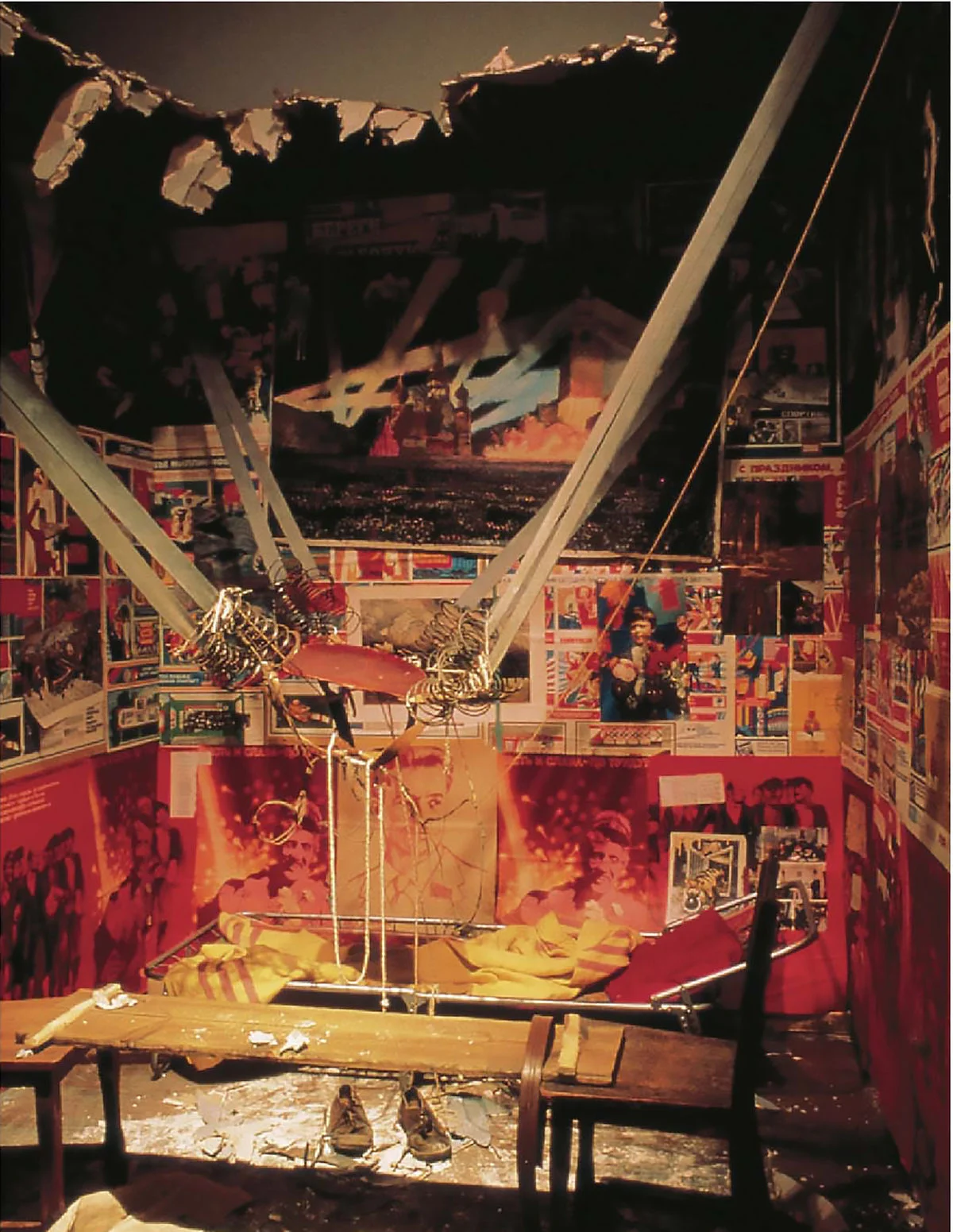

Read MoreThis extensive exhibition of Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s work will explore the theme of failed utopia. Taking its cue from the title of Ilya Kabakov’s text Not Everyone Will be Taken into the Future, the exhibition will present Ilya Kabakov’s paintings, drawings, and albums made in Moscow from the 1950s to the 1980s before he emigrated to the United States. The exhibition will also show the ‘total’ installations made in collaboration with Emilia from 1989 to the present, which evoke the history and visual culture of the Soviet Union.

Read MoreThe husband-and-wife team is now receiving widespread recognition and acclaim, thanks to an exhibition at Pace Gallery and a documentary at Film Forum.

It is turning out to be a banner year for Emilia and Ilya Kabakov, perhaps Russia’s best-known living artists. Although superstars overseas—commanding multimillion-dollar prices for their canvases, sculptures, and installations—the conceptualist pair is less known in the U.S., despite having spent the past two decades on Manhattan and Long Island.

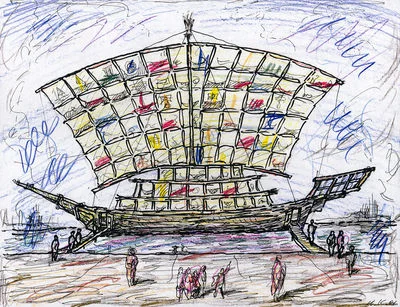

Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, in a joint collaboration with Studio in a School, will present The “Ship of Tolerance,” in Brooklyn Bridge Park on September 27, 2013 as part of the 17th annual DUMBO Arts Festival. The work will remain on view on the Brooklyn waterfront until October 6th.

Read More“Not everyone will be taken into the future”, reads the LED sign on the vanishing metro. Even as visitors step into the gallery they find themselves stranded on an empty platform watching the train as it draws away from them, disappearing through the tunnel of a gallery wall. A few discarded paintings are left, tumbled, on the tracks behind it; abandoned, along with you, are old plastic sheeting and a cheese grater.

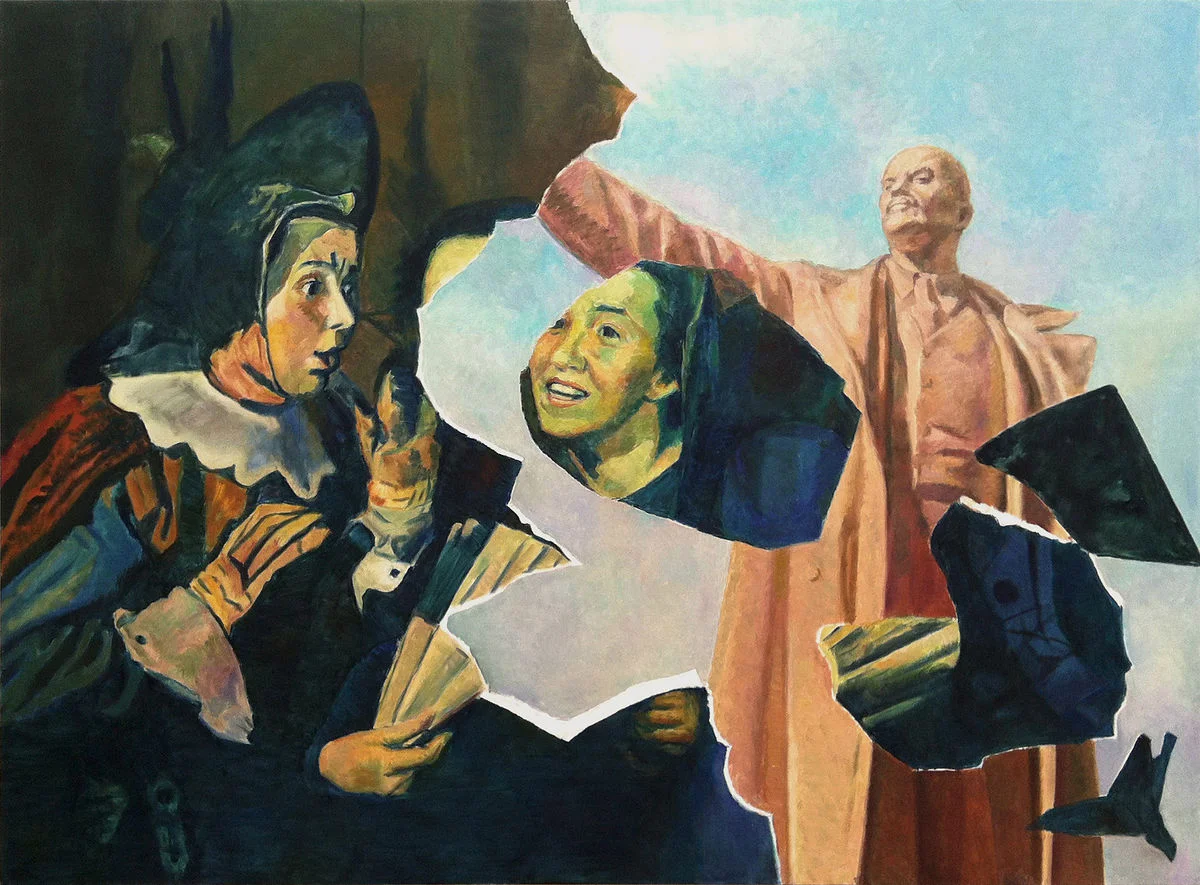

Read MoreRussia’s best-known contemporary artists are American citizens who haven’t lived in the motherland since the Eighties. Yet just about everything in their first major British exhibition (he’s84, she’s 72) refers back to the old Soviet Union: large conceptual paintings based on bureaucratic paperwork, painted mash-ups of socialist realism and the Old Masters, large-scale “total” installations in which old-school Soviet collective apartments become places of simultaneous bleakness and wonder.

Read MoreNot Everyone Will Be Taken Into The Future, Tate Modern’s Ilya and Emilia Kabakov exhibition, opens with a self-portrait of Ilya dressed as an airman and closes with models and drawings of angels. Fantasies of flight, freedom, and weightlessness permeate the show. Look through a monocular lens and you can see tiny men in space; peer in through a boarded-up doorway and you will discover that a Muscovite has apparently ejected himself into the stratosphere through his apartment roof; there are winged harnesses with sets of instructions, and fables of flight illustrated like everyday school books. All are, in some way, counterweights to the claustrophobia, abjection, and self-policing that characterized the artists’ experience of life in the USSR. Ilya’s self-portrait in a flying helmet was painted in 1962, the year after Yuri Gagarin became the first man to orbit the earth. Kabakov was 28, married with a baby daughter, and working officially as an illustrator of children’s books. He had already, for some years, been involved in the production of clandestine ‘unofficial’ artworks that deviated from the Soviet Realist style.

Read MoreShe was born in 1902 and died in 1987. She lived through the Russian revolution, the civil war and the famine of 1921-22 that killed her father. Then there was the second world war, and finally glasnost and perestroika. Her name was Bertha Urievna Solodukhina and her life was a constant struggle. She endured antisemitic abuse, homelessness and a string of precarious jobs as she tried to raise a son alone.

Read MoreThe Kabakovs’ exhibition made me thank my lucky stars I was not born in the Soviet Union. A recurring theme of their work is the desire to escape – from the hunger and poverty caused by incompetence and poor planning, and the doublethink required to survive under a regime that became ever more repressive the greater and more obvious its failings.

Read MoreThe Kabakovs are amongst the most celebrated artists of their generation, widely known for their large-scale installations and use of fictional personas. Critiquing the conventions of art history and drawing upon the visual culture of the former Soviet Union – from dreary communal apartments to propaganda art and its highly optimistic depictions of Soviet life – their work addresses universal ideas of utopia and fantasy; hope and fear.

Read MoreThe Kabakovs are amongst the most celebrated artists of their generation, widely known for their large-scale installations and use of fictional personas. Critiquing the conventions of art history and drawing upon the visual culture of the former Soviet Union – from dreary communal apartments to propaganda art and its highly optimistic depictions of Soviet life – their work addresses universal ideas of utopia and fantasy; hope and fear.

Read MoreAn especially poignant allegorical work by Russian-born artists Ilya and Emilia Kabakov sits within an open, sun-drenched grassy knoll. “The Arch of Life” (2016) is modest compared with this renowned couple’s more monumental installations. Yet five figures set upon an arch carry the full weight of their vision of pathos and resilience: An egg hatches a human head; a vulnerable youth shows bravado as he crawls on hands and knees wearing a lion mask; a third figure bearing a light-filled box on his back represents hope through adversity; and a fourth torso, sorrowfully draped over two sides of a wall, suggests the universal plight of those unable to survive. The final figure, surrounded by the weight of his agony, is in a state of collapse.

Read MoreThroughout this year, ambitious projects will be unveiled all over America — from an artistic jungle gym in Miami to a pirate ship docking in Northern California — and they don’t cost anything to see. One of them is the installation by world famous artists Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, “Pirate Ship.”

Read MoreKabakov’s installation “The Great Axis” (1984) includes a monumental painting showing a narrow feathery band of green along the bottom and a similar band of blue along the top, with a flat expanse of white paint in between; a thin black line runs diagonally across it, its opposing ends marked with the words “sky” and “earth.” A text panel explains that “The Great Axis” links the sky with the earth; if one fastens the end of the axis on earth, he’ll be able to move the sky, and vice versa. Nearby, Kabakov’s drawings feature short fragments of text rendered in watercolor and ink; reading them is like listening to a discordant chorus of many voices forming the imaginary audience of “The Great Axis.” Some sound curious, others perplexed or hostile, yet others completely indifferent: “Why do they need the labels? It’s all clear as it is”

Read MoreEmilia Kabakov, who collaborates with her husband, Russian conceptual artist Ilya Kabakov, talks about working together, their exhibition at Pace Gallery, and other projects they are planning.

Read More