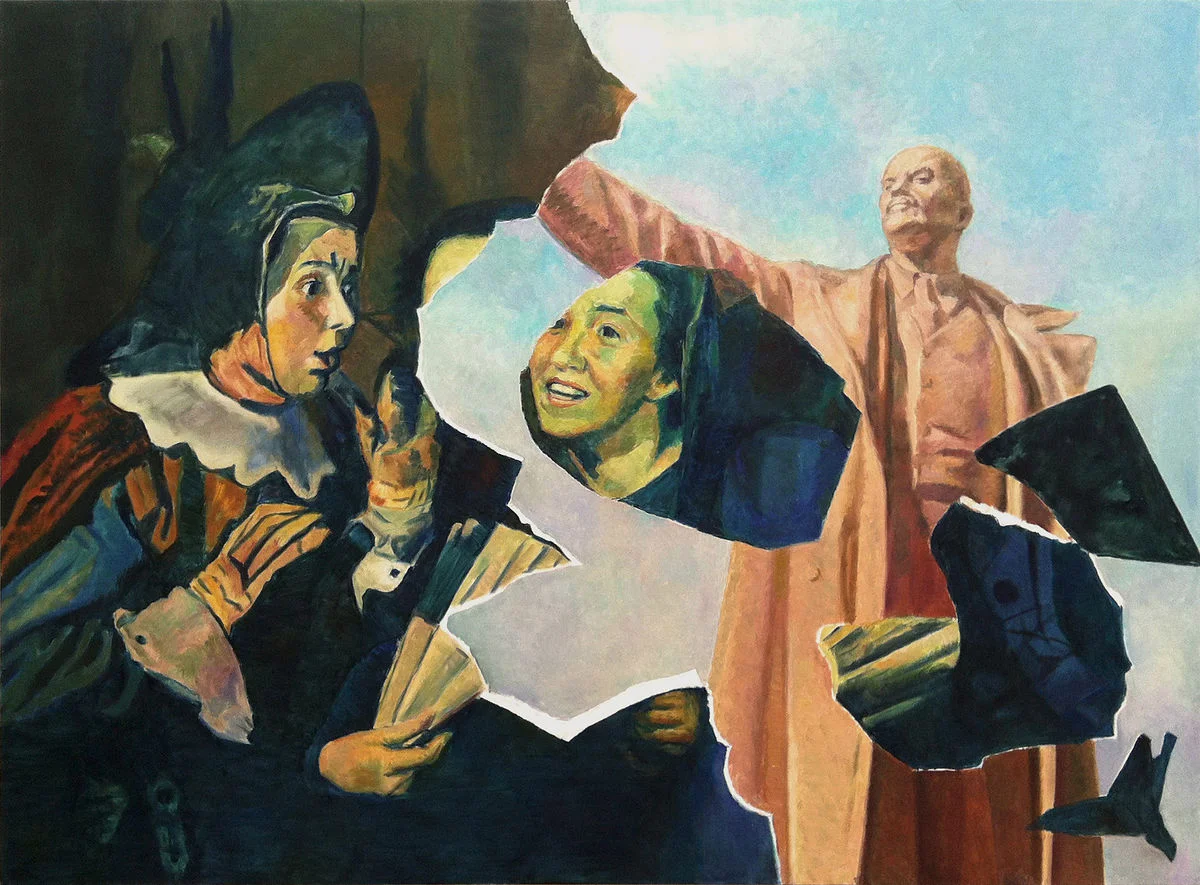

Not Everyone Will Be Taken Into The Future, Tate Modern’s Ilya and Emilia Kabakov exhibition, opens with a self-portrait of Ilya dressed as an airman and closes with models and drawings of angels. Fantasies of flight, freedom, and weightlessness permeate the show. Look through a monocular lens and you can see tiny men in space; peer in through a boarded-up doorway and you will discover that a Muscovite has apparently ejected himself into the stratosphere through his apartment roof; there are winged harnesses with sets of instructions, and fables of flight illustrated like everyday school books. All are, in some way, counterweights to the claustrophobia, abjection, and self-policing that characterized the artists’ experience of life in the USSR. Ilya’s self-portrait in a flying helmet was painted in 1962, the year after Yuri Gagarin became the first man to orbit the earth. Kabakov was 28, married with a baby daughter, and working officially as an illustrator of children’s books. He had already, for some years, been involved in the production of clandestine ‘unofficial’ artworks that deviated from the Soviet Realist style.

Read More